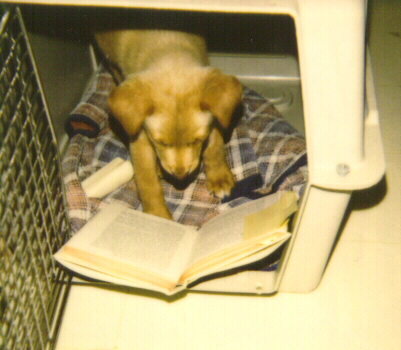

by

Hav'too, D.Og.

(Doctor of Obstreperous-generalities)

Marketing Educator special guest editor

I once thought that I could never be a college student. I am evolutionary challenged, I do not speak very clearly (though I do not drool), and without an opposing thumb, my typing skills leave a great deal to be desired. Yet three unrelated events make me see that not only should I enroll, I should get top grades based on my motivation, drive and desire to work.

In the first instance, a marketing teacher told me of his late night calls from the mother of a student who failed his class. While the caller's daughter was seldom absent, she exhibited the cognitive activity of a beanie baby. When called upon for class discussion, she just stared at the teacher. For most exams, she turned in a blank paper, as she did with most questions on the comprehensive final. Yet the mother argued that the F grade would force an additional term of work for graduation, something the family could not afford. "I am a teacher, too," she said, "and I know that you must sometimes give a passing grade for the effort and not just what the student does." Of course, universities recognize that faculty sometimes do this and have a name for it: capricious grading.

More recently, news attention to military and basic training reported that the physical tests for women were weaker than those for men. A base commander told the interviewer that "You must understand that the women's effort to meet their different standards is the same as the effort required for the men to meet theirs." I had previously thought that standards meant a measure of needed performance, or else they were meaningless.

The third but older story drove it home. Last year, a high school swimming star was falling short of the National Collegiate Athletic Association policies for academic eligibility and could not compete during his first year of college. His highly publicized response was to assert that the rules should not apply to him because he is learning disabled, in effect claiming high school course credit for work he did not do. At the same time, a gymnastics champion had similar concerns, with hers a disability which "limits her long-term memory." No one mentioned that such a problem should raise doubts as to whether she carried enough background from high school to do college work.

In all these stories, people are asking for an "A for effort."

Regardless

of performance, they wanted the credit or grades because of who they

are

or how hard they try. It is no different than raising scores because

the

person is good looking, and it implies that a motivated student

acquires

the learning experience necessary for future success by contagion

regardless

of performance. By this standard, I should be considered a top student

-- I prove my drive and motivation when I am  chasing

tennis balls in Alabama in August -- but I am not so chromosomally-limited

and follicle over-endowed to have my mind clouded by such delusions

that

I should get course credit.

chasing

tennis balls in Alabama in August -- but I am not so chromosomally-limited

and follicle over-endowed to have my mind clouded by such delusions

that

I should get course credit.

In general, there are three basic factors in a student's success in higher education: innate ability, the basic tools or background to handle the material, and motivation. Sometimes extra output in one area can compensate for weaknesses or limitations in another. It is totally acceptable to give a learning disabled person help so he or she could learn the material. It may take an extra effort, but it is no different than a lecturer using a special microphone that directly feeds the hearing impaired person's hearing aid or finding a textbook reader for a visually challenged student. However, it is another matter completely to assert that because a person is different or disabled he or she should get credit for what they did not do. And some people just can't handle higher education. Standards mean that work has been done.

Unfortunately, many faculty see students that they know are not disabled who fake an impairment in order to get a diagnosis. They say they want to have the competitive edge "in case they need it." Student advisors at many schools report that able-bodied men and women are asking how to "get into the disability program" (apparently without evidence of any real disability) so they could get first pick on class schedules.

Higher education magazine Change briefly noted the

(supposedly)

true story of the student who told the teacher he had a disability.

When

asked what it was, he said, "I'm not sure [but] I seem to have trouble

thinking." As one athletic department  counselor

told my friend, many of her charges have the "learning disability" of

being

academically lazy. Once the rules said that learning disabled students

could take the ACT tests without a time limit, there was a sudden

increase

in students claiming the disability. A friend showed me a notification

on a student in his class who needed oral exams because of difficulty

reading

and writing responses, and that the student "prefers" multiple-choice

exams

since he has difficulty expressing himself. We all wonder what such a

student

would have learned after four years of college; the more sarcastic

among

us notes that this means illiteracy is now a learning disability.

counselor

told my friend, many of her charges have the "learning disability" of

being

academically lazy. Once the rules said that learning disabled students

could take the ACT tests without a time limit, there was a sudden

increase

in students claiming the disability. A friend showed me a notification

on a student in his class who needed oral exams because of difficulty

reading

and writing responses, and that the student "prefers" multiple-choice

exams

since he has difficulty expressing himself. We all wonder what such a

student

would have learned after four years of college; the more sarcastic

among

us notes that this means illiteracy is now a learning disability.

No one wants to prevent a disabled person of any kind from acquiring

an academic experience. But in school, the course credit and grade is a

statement of learning, requiring the ability to read and write and

express

ideas. And that lets me out.