Jack Birner and Rudy van Zijp, eds.

Hayek, Coordination and Evolution:

His Legacy in Philosophy, Politics, Economics, and

the History of Ideas

London: Routledge, 1994, pp. 109-125

Hayekian Triangles and Beyond

Roger W. Garrison

The lectures that F. A. Hayek delivered at the London School of Economics

in the early 1930s were punctuated with triangles—triangles of a sort his

audience had never before seen. Now, more than sixty years after those

lectures were published as Prices and Production (1931), the triangles

still hold the key to understanding Hayekian macroeconomics. What exactly

did Hayek see in them? Why could most of his audience see nothing at all

in them? Satisfying answers to these two questions can go a long way towards

identifying the core differences between Austrian and Anglo-American macroeconomics.

Considering a third question

can add significance to our answer. What relevance do the ideas that Hayek

hung on those triangles have today? The lectures were written at a time

when Hayek and the rest of the profession were contemplating the dramatic

economic boom of the 1920s and the subsequent depression that had yet to

find its bottom. The early 1990s find the profession in similar circumstances—contemplating

the dramatic bull market of the 1980s and wondering if and how the current

recession is related. It would be a mistake to assume that Hayek's triangulation

as applied to the earlier episode applies in some wholesale fashion to

the current one, but it would be a greater mistake to assume that Hayek's

insights have no current application of all.

Hayek's theory of boom and

bust can be generalized so as to increase its plausibility as an account

of the 1920s and 1930s and give it new life in accounting for the 1980s

and 1990s. After making the appropriate conceptual and institutional adjustments,

the story in Prices and Production can be retold in a way that sheds

light on contermporary macroeconomic problems. Also, reconsidering the

triangles—as Hayek employed them then and as present-day Hayekians might

employ them now—helps to put in perspective the macroeconomics of the intervening

years which grew out of the Keynesian revolution.

The Macroeconomic Significance of the Triangles

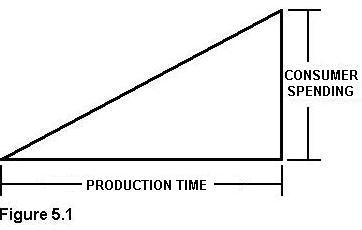

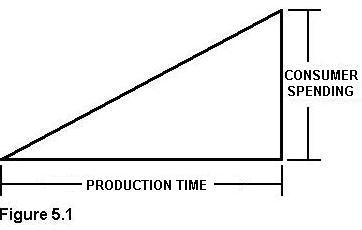

The Hayekian triangle, as described in Hayek's second lecture (Hayek,

1967, pp. 36-47), is a heuristic device that gives analytical legs to a

theory of business cycles first offered by Ludwig von Mises (1953, pp.

339-366). A right triangle depicts the macroeconomy as having a value dimension

and a time dimension. It represents at the highest level of abstraction

the economy's production process and the consumer goods that flow from

it. One leg of the triangle represents dollar-denominated spending on consumer

goods; the other leg represents the time dimension that characterizes the

production process (Figure 5.1). In a fundamental sense, the Hayekian triangles

in their various configurations illustrate a trade-off recognized by Carl

Menger and emplasized by Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. At a given point in

time and in the absence of resource idleness, investment is made at the

expense of consumption.  Investment,

which entails the commitment of resources to a time-consuming production

process, adds to the time dimension of the economy's structure of production.

To allow for investment, consumption must fall initially in both nominal

and real terms. Once the capital restructuring is complete, the corresponding

level of consumption is higher in real terms than its initial level. The

nominal level of consumption spending, however, is lower than its initial

level because a greater proportion of total spending is devoted to the

maintenance of a more time-consuming production structure. Investment,

which entails the commitment of resources to a time-consuming production

process, adds to the time dimension of the economy's structure of production.

To allow for investment, consumption must fall initially in both nominal

and real terms. Once the capital restructuring is complete, the corresponding

level of consumption is higher in real terms than its initial level. The

nominal level of consumption spending, however, is lower than its initial

level because a greater proportion of total spending is devoted to the

maintenance of a more time-consuming production structure.

The relative length's of

the triangle's two legs, then, represent the inverse relationship between

nominal consumption spending and nominal non-consumption spending—the latter

as reflected by the time dimension of the economy's capital structure.

Hayek makes use of several heuristic assumptions that cause production

time and non-consumption spending to be more tightly linked in his graphics

than in reality. He assumes, for instance, that the production process

consists of stages of production such that output of one stage sells as

input for the next and that the number of stages varies directly with production

time. For the purpose of defining the triangles, the quantity of money

and the velocity of circulation—and hence the product MV—are assumed

constant. (Episodes of monetary expansion, however, provide the most interesting

and relevant circumstances for application of the graphics.)

The Hayekian triangles can

change in shape in circumstances of a constant MV—and hence a constant

PQ,

where Q is understood to include the sum of the outputs of each

stage of production including the final stage whose output is consumption

goods. The Hayekian Q, then, lies somewhere between the Fisherian

T,

which stands for total transactions and the Friedmanian Y, which

stands for income or final output (consumption plus net investment); the

corresponding V lies somewhere between the transactions velocity

and the income velocity.

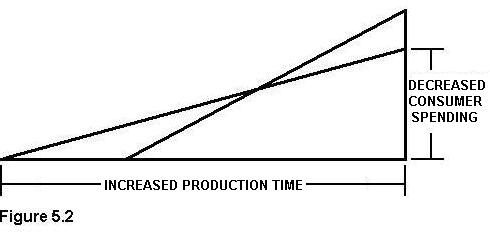

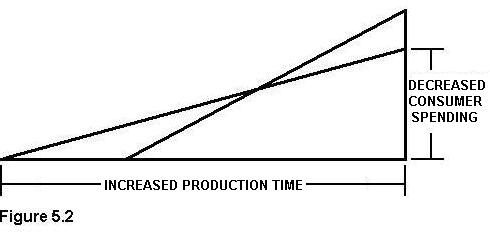

The basis for a change in

the shape of the triangle is a hypothetical preference change within

the output aggregate. Suppose that consumers become more future oriented.

Their time preferences—to use the Austrian term—are lower than before.

In the first instance, this preference change means a decrease in demand

for current consumption and an increase in saving. In the Austrian formulation,

saving means more than simply not consuming. Income earners do not just

save; they save-up-for-something. Saving-up-for-something is another terminological

in-betweener lying somewhere between the conventional polar concepts of

saving as a flow and savings as a stock. Increased saving in the Austrian

formulation gets translated through market mechanisms and entrepreneurial

foresight into higher demands for inputs in the relative early stages of

production. The demand for output as a whole, then, is neither higher nor

lower than before the preference change. Rather, the pattern of demand

has changed in a way that is conveniently depicted by a Hayekian triangle

whose consumer-spending leg has become shorter and whose production-time

lag has become longer (Figure 5.2).

The height of the hypotenuse

of the reconfigured triangle measured at each stage of production along

the production-time leg shows (1) that the demand for input is reduced

in the final and late stages  of

production, (2) that the extent of the reduction diminishes as stages further

removed from consumption are considered, (3) that stages remote from consumption

experience an increased demand for input and (4) that stages of production

more remote than had existed before have been created anew. The slope of

the hypotenuse, now less steep than before, reflects a lower rate on interest

corresponding to the reduced time preference. of

production, (2) that the extent of the reduction diminishes as stages further

removed from consumption are considered, (3) that stages remote from consumption

experience an increased demand for input and (4) that stages of production

more remote than had existed before have been created anew. The slope of

the hypotenuse, now less steep than before, reflects a lower rate on interest

corresponding to the reduced time preference.

Reduced time preferences

mean a smaller time discount on future consumption. Consumers are more

willing to sacrifice consumption goods available now and in the immediate

future for consumption goods available in the relatively remote future.

Tailoring production plans to consumption preferences requires that the

structure of production be modified in precisely the way depicted by the

change in the Hayekian triangle just described. Hayek went beyond determining

what changes in the structure of production were required by the preference

change to identifying, in his third lecture, the market mechanisms that

could allocate resources among the stages of production in conformity with

the time preferences of consumers. Lower time preferences means increased

saving and hence a lower rate of interest. The lower interest rate drives

down the competitive gross profit margin in each stage of production. That

is, for each stage input prices are bid up in relationship to output prices.

the cumulative effect of this relative-price adjustment increases with

increased remoteness from the final stage. Accordingly, resources are shifted

out of late stages and into early stages in response to the lower time

preferences.

It is easy to fault Hayek

and his triangles for sins of omission. What about durable capital and

consumer durables? What about changes in the degree of vertical integration?

What about instances of input-output circularity such as coal as an input

in the production of steel and steel as an input in the production of coal?

The realization that there are many aspects of a modern decentralized capitalist

economy not captured by a triangle should come as no surprise. What is

surprising is how much these triangles do depict or imply. Implicit, for

instance, is the notion that the structure of production is characterized

by some—but not complete—specificity: If all capital goods were wholly

non-specific, then no structure could be defined; if every capital good

were completely specific, then no modification could be made. The notion

of stage-specific capital implies a certain intertemporal complementarity

that characterizes the structure of production. Complementarity through

time gives special significance to the time element in the production process—which

was so emphasized by Menger and Böhm-Bawerk.

Treating the problem of

intertemporal allocation of resources in terms of the economy's capital

structure keeps the entrepreneurial element of the argument in perspective.

In the alternative Anglo-American formulations, capital theory is suppressed.

Hence, the concept of investment, which is defined as the rate of change

in the capital stock, is not well anchored, and doubts that saving will

get translated into investment dominate in discussions of both theory and

policy. The Hayekian triangles are a constant reminder that a certain amount

of entrepreneurial foresight governing the intertemporal allocation of

resources is essential to the functioning of a capitalist economy whether

or not there are any net additions to the economy's capital stock. If market

mechanisms governing intertemporal allocation are working properly, saving

and investment pose no special problems. Changes in saving propensities

have a direct impact on the rate interest. Market mechanisms together with

entrepreneurial foresight continue to operate as before—only now under

different credit conditions—to allocate capital and other resources among

the stages of production.

The ultimate effect of a

change in the rate of interest on the capital structure is seen as a difference

in shape between the initial and subsequent Hayekian triangle. In Prices

and Production, Hayek did not treat in any detail the issues of the

traverse, as john Hicks (1965. pp. 183-197) was later to call it. The intertemporal

profile of output during the capital restructuring—the traverse—is dependent

on a myriad of details involving the specifics of technology and the intertemporal

complementarities and substitutabilities that characterized the existing

capital structure. Implicit in Hayek's application of the triangle, however,

is one critical distinction. Depending upon what caused the interest rate

to fall, the traverse may or may not be consistent with an actual completion

of the capital restructuring. In summary terms, we can say that if the

lower interest rate is attributable to new economic realities, particularly

if it reflects lower time preferences of consumers, then the traverse will

be consistent with completing the process of capital restructuring. If,

instead, the lower interest rate is attributable to new economic policies,

particularly if it reflects credit expansion by the central bank, then

the traverse will be inconsistent with completing the process of capital

restructuring. The preference-induced process is one of economic growth;

the policy-induced process is one of boom and bust (Hayek, 1967, pp. 50-60).

Hayekian Shapes and Keynesian Sizes

Capital theory in which value is played off against time should not

have been totally foreign to Hayek's English audience. A half-century before

Hayek molded his lectures around those triangles, an essentially equivalent

construction, not then known by Hayek (1967, p. 38), had been offered by

William Stanley Jevons. The Jevonian investment figures, which were the

core of Jevons's chapter on capital (Jevons, 1970, pp. 225-253), showed

capital value rising linearly with time as production proceeded from inception

to completion. What was foreign to the English audience was the use of

the triangular construction as the basis for macroeconomic theorizing and

for theorizing, in particular, about boom and bust.

Capital theory is complex

in its own right—as are most theories of cyclical variation. Hayek's attempt

to present a capital-based theory of cyclical variation in an early stage

of development involved the compounding of complexity with complexity.

It is not at all surprising, then, that these ideas would seem foreign

to most and bewildering to many. Reflecting years later on Prices and

Production, Hicks remarked that the book "was in English, but it was

not English economics (Hicks, 1967, p. 204). Joan Robinson, who had heard

Hayek lecture at Cambridge on his way to the London School, referred to

Hayek's theory as a "pitiful state of confusion," and believed that his

whole argument "consisted in confusing the current rate of investment with

the total stock of capital goods" (Robinson, 1972, p. 2).

John Maynard Keynes (1931)

reviewed Hayek's book in what was purportedly a reply to Hayek's critique

of Keynes's Treatise on Money. Piero Sraffa (1932) defended his

own views on production and distribution theory in what was purportedly

a review of Hayek's book. Both Keynes and Sraffa were unreceptive and even

hostile to the ideas in Prices and Production. After reporting his

own early fascination with Hayekian theory, Nicholas Kaldor (1942) reassessed

Prices

and Production in the light of subsequent application of the theory.

He concluded that the basic ideas in that book must be wrong and referred

jeeringly to Hayek's capital-based theory of boom and bust as the "Concertina

Effect."

Some English economists,

notably Lionel Robbins (1934) and to a lesser extent John Hicks and Abba

Lerner, were persuaded, at least temporarily, of the merit of Hayek's theory.

But the general direction the economics profession was taking at the time

was not conducive to the acceptance of a capital-based macroeconomics.

The very complexity of a capital structure in macroeconomic disequilibrium

seemed to be grounds for sending value and capital theory in one direction

and macroeconomics in another. The breaking away of macroeconomics from

consideration of capital structure became complete with the publication

in 1936 of Keynes's General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.

If the assumptions Hayek

invoked to make his theory tractable seem severe, the ones Keynes invoked

in Chapter 4 of his General Theory should seem more so. Keynes's

assumption of a fixed structure of industry effectively took the triangles

out of play. So long as fixity characterizes the relationship among the

stages of production, questions about the intertemporal allocation of resources

are moot, and scope for intertemoral discoordination nil. With a given

ratio of the value leg and the time leg of the Hayekian triangle, the issue

of the triangle's shape, so emphasized by Hayek, gave way in Keynes's own

theorizing to the issue of the triangle's size. Scope for variation in

size is simply the mirror image of scope for variation in resource idleness.

The capital-based Hayekian

vision and the capital-free Keynesian vision can be put into perspective

with the aid of a simple production-possibilities frontier in which investment

is traded off against consumption. So long as investment is positive, the

frontier itself moves outwards from one period to the next enabling higher

levels of both investment and consumption. The two visions differ fundamentally

in terms of the assumed initial conditions, or starting point, underlying

the theory and in terms of acknowledged market forces that propel or constrain

movement from those initial conditions.

Hayek took some point on

the frontier as his starting point and concerned himself with market processes

and central bank policies that move the economy along the frontier in the

direction of more investment. he argued, in effect, that if lower time

preferences—and hence a reduction in the natural rate of interest—underlie

the shift of resources away from consumption and towards investment, the

intertemporal market process governed largely by the interest rate would

move the economy along the frontier facilitating a more rapid expansion

of the frontier itself. If, however, credit expansion—and hence a suppression

of the interest rate below its natural level—underlies the shift of resources

in the direction of more investment, then the market process, forced in

the direction of more investment, would create internal tensions within

the capital structure which ultimately would throw the economy off the

production possibilities curve in the direction of resource idleness.

Keynes took some point interior

to the frontier as his starting point and concerned himself with fiscal

and monetary policies as well as institutional and social reforms that

may facilitate movement back to the frontier. Prospects for a market-driven

mobilization of idle resources were ruled out in his preliminary chapters.

With capital theory suppressed, concerns about which particular point on

the frontier to aim at were secondary—if that—to the basic concern of eliminating

resource idleness. The idea of a natural rate of interest and implied mix

of investment and consumption spending held no significance for Keynes

(1964, p. 373). He held, in effect, that there are as many natural rates

as there are combinations of demands that put the economy on its production

possibilities frontier. Market forces within the capital structure that

may favor one point on the frontier over another on the basis of intertemporal

consumption preferences were no part of his theory. In sum, Hayek offered

a capital-based explanation of how the economy got into a depression; Keynes

offered a capital-free prescription for getting out.

The Economics of Credit Controls and Credit Expansion

Abstract as the Hayekian triangles are, their application has strong

counterparts in basic microeconomic theory. The macroeconomic flavor can

be retained by virtue of the explicit accounting of the time element in

the production process which may involve scope for economywide intertemporal

discoordination. Alternative credit-market interventions can be considered

in the context of basic supply-and-demand analysis. The particular intervention,

conceived in microeconomic terms, may or may not have significant macroeconomic

consequences depending upon whether or not there is scope for a systematic

discoordiantion within the structure of production.

First, consider the economics

of credit control in the form of an interest-rate ceiling. So long as the

legal maximum is below the market-clearing rate of interest, the credit

market will be cut short. The supply of credit becomes the binding constraint.

Savers who would have been willing to supply funds at interest rates between

the legal-maximum rate and the market-clearing rate will now find additional

consumption more attractive. The credit shortage reflects the many would-be

borrowers eager to take advantage of investment opportunities made attractive

by the low interest rate—which is to say, opportunities in the relative

early stages of production. The incentives created by credit control, then

push in opposite directions: erstwhile savers prefer to increase their

current rate of consumption while investors become—or at least would like

to become—more future oriented.

By the very nature of the

price ceilings, however, the constrained preferences do not get translated

into realities. There is no scope even for the beginnings of a process

of capital restructuring as would be guided by a low market-clearing rate

of interest. In fact, to the extent that black markets or grey markets,

which flout or skirt the legal restriction, come into being, the corresponding

rate of interest will be demand-determined. Some demanders of credit who

would have been shut out by the legislated ceiling are accommodated but

at an interest rate above the old market-clearing rate. This high rate

of interest puts a premium on time an channels resources into the relative

late stages of production. The ultimate result is that both the time pattern

of production and the time pattern of consumption are less future oriented

than before the imposition of the interest-rate ceiling.

Second, consider the imposition

of an interest-rate ceiling accompanied with a further intervention to

prevent the credit shortage from materializing immediately. Suppose that

the difference between credit supplied and credit demanded at the legal

maximum is made up for by credit creation. The creating and lending of

money to fill the gap between supply and demand has the effect of papering

over the shortage. It keeps the discrepancy in incentives between the two

sides of the market from showing itself immediately.

If borrowers were to respond

to the combination of a ceiling rate and abundant credit in the same way

they would respond to a low market rate, resources would be allocated away

from late stages of production and into the early stages. As this capital

restructuring is underway, income earners would be turning from saving

to consumption in the face of the interest-rate ceiling. The market linkages

through which the production process is tailored to consumption preferences,

however, are not so tight as to curtail the capital restructuring in its

incipiency. The time element inherent in the production process translates

directly into scope for capital restructuring even in the absence of any

change in consumption preferences. But the discrepancy in incentives means

that the capital restructuring in necessarily ill-fated. Unavoidably, there

will be a clash between producers and consumers as the restructuring process

goes forward. Misallocations revealed in the clash will require liquidation

and reallocations more consistent with consumer preferences and the interest-rate

ceiling.

It is doubtful that investors

would actually respond to a ceiling rate—even with the would-be credit

shortage papered over with credit creation—in the same way that would respond

to a low market rate. The very enactment of the interest-rate ceiling would

have a certain announcement effect that would warn borrowers away from

business-as-usual investment strategies. The credit creation, however,

initially described as "further intervention" aimed at concealing temporarily

the effects of the interest-rate ceiling, actually makes the interest-rate

ceiling largely redundant. That is, the expansion of credit by itself has

the effect of reducing the interest rate as it adds to the supply of loanable

funds. The allocational consequences, somewhat implausible in the face

of a legislated interest-rate ceiling, gain in plausibility—and in historical

relevance—when attributed to credit expansion alone.

Finally, then, consider

the economics of credit expansion. The differences to be highlighted by

considering this particular sequence of interventions are differences in

announcement effects and in expectations about future credit-market conditions.

Unlike an interest-rate ceiling as might be imposed by the legislature,

credit expansion orchestrated by the central bank can be initiated without

public debate and without any strong announcement effect. Borrowers are

likely to respond to favorable credit conditions attributable to central-bank

policy in about the same way they would have responded to favorable credit

conditions attributable to increased saving. In fact, many borrowers would

not bother to find answers or even to ask questions about the basis for

the lower interest rate. Yet, the policy-induced lower rate creates the

same discrepancy of incentives as does an interest-rate ceiling. Savers

save less, and borrowers borrow more, with the difference between saving

an borrowing being made up by credit expansion.

Business-as-usual investment

decisions under favorable credit conditions are the makings of an economic

boom. Increased funds in the hands of investors and the increased profit

prospects in long-term projects allow for increased employment opportunities

as resources are drawn away from late stages of production and into earlier

stages. The multi-stage production process as depicted by the Hayekian

triangles provides scope for extensive capital restructuring in the direction

of a more time-consuming production process despite the actual reduction

in saving. The tug-of-war between producers and consumers implicit in the

policy-induced economic expansion does not produce a victor in a timely

manner. It is a tug-of-war with and expandable rope.

If the business community

continues to respond to the credit expansion as if favorable credit conditions

will last indefinitely, then the duration of the boom will be limited by

the time element in the production process itself. Outputs of earlier stages

feed successively into subsequent stages. At some stage in this process,

the viability of the policy-induced capital restructuring comes into question.

Capital and labor resources complementary to those already committed to

earlier stages are in short supply (Hayek, 1967, pp. 85-91). The bidding

up of input prices in the late stages of production impinges on credit

markets as well. So-called distress borrowing puts an upward pressure on

interest rates wholly separate from any inflation premium attributable

to credit expansion.

In the final throes of a

policy-induced boom, the role of the central bank becomes more evident

and more visible. Will the central bank supply additional credit, which

will more fully satisfy each demand in nominal terms but will translate

generally into higher resource prices rather than more successful bidding?

Or, will the central bank curtail credit to avoid still further misallocation

of resources and a general price inflation? The tug-of-war between producers

and consumers becomes, from the perspective of the central bank, a tiger

by the tail. Both bulls and bears engage in speculative transactions on

the basis of their guesses about how long the central bank will hang on

and just when it will let go.

Economists who do not theorize

in terms of a capital structure and who question the meaning or significance

of the natural rate on interest, tend to see little harm—and may see great

benefit—in credit expansion. Most of those same economists would see as

foolish, wasteful, and counterproductive any attempt to impose a price

ceiling on any market and especially an attempt to impose an interest-rate

ceiling on credit markets. Yet, the key difference emphasized above between

an interest-rate ceiling and credit expansion in the context of a multi-stage

capital structure is that the perversities of the interest-rate ceiling

manifest themselves more directly and more quickly and, although disruptive,

are less so than the alternative policy of credit expansion. The perversities

of a credit-induced boom are obscured by the initial positive effects of

credit expansion, the time element that separates credit expansion from

its negative effects, and the complexity of the capital theory needed to

make the theoretical connection between expansion and crisis.

Three Components of the Interest Rate

Attention to the time element in the capital structure allows the message

in Hayek's Prices and Production to be generalized and then adapted

so as to apply in contexts other than the one that inspired his London

lectures. Production time inherent in the multi-stage production process

can put a lag between intervention in credit markets and the ultimate consequences

on that intervention. The particular intervention of concern to Hayek,

credit expansion, affected the capital structure's intertemporal orientation.

The cheap credit favored a reallocation of resources among the stages of

production that was inconsistent with intertemporal consumer preferences.

More specifically, the artificially low rate on interest caused production

plans to become more future oriented and consumption plans to be come less

so.

Other sorts of intervention

that might have lagged consequences on an economywide scale can be identified

by taking the interest rate to be the key market signal that translates

cause into lagged effect and considering the individual components of the

market rate on interest. To this end, it is convenient to conceive of the

market rate as consisting of three components: an underlying time discount,

an inflation premium, and a risk premium. Hayek's triangulation in the

early 1930s was based squarely on the first component.

By the 1960s the focus of

macroeconomists had shifted from the first component to the second. Practiced

use of monetary tools as economic stimulants—however temporary the actual

effects—gave increasing importance to the role of expectations. Scope for

a significant discrepancy between expected and actual inflation rates resulted

in macroeconomic constructions that featured the inflation premium. Arguably,

the most interesting consequences of imperfectly anticipated inflation

are those that manifest themselves as the misallocation of capital and

labor among the stages of production as might be depicted by Hayekian triangles.

But by the time the problem of inflation had captured the attention of

modern macroeconomists, capital theory had been in eclipse for more than

two decades.

The Keynesian revolution

had so weakened the perceived link between capital and interest that it

became commonplace to theorize in terms of the level on employment in the

context of a given capital structure. Monetary expansion, which has its

most direct effects in credit markets and on interest rates, came to be

analyzed in terms of labor markets and wage rates. This shift in focus

was seen as a glaring incongruity to economists who learned their macroeconomics

from Hayek but was second nature to economists who had long since left

capital theory behind.

The nature and significance

of the inverse relationship between the inflation rate and the level of

employment as depicted by the Phillips curve was derived from differences

in the abilities of employers and employees in forming relevant expectations

and on differences in the way market participants, broadly conceived, adjust

their expectations about inflation (Friedman, 1976). The first difference

governed the strength of the short-run trade-off between inflation and

unemployment; the second difference governed the length of the short run.

What came to be the conventional account of the consequences of monetary

expansion traces the movement along a short-run Phillips curve, which reflects

given expectations, then allows for a shifting of the curve to reflect

a change in expectations. The adjustment process involves a temporary decrease

in the unemployment rate as wage adjustments lag behind price adjustments

followed by a permanent increase in the inflation rate as the general level

of prices catches up to the expanding money supply. Except for occasional

reference to temporary and wholly incidental disturbances affecting stock-flow

relationships in markets for financial and real assets, business-cycle

theory based upon short-run/long-run Phillips curve dynamics takes no account

of capital misallocation. The critical time element, which was a fundamental

aspect of the capital-based theory of Hayek's theory, was retained in the

tenuous form of time-consuming adjustments—accomplished differentially

by employers and employees—of perceptions to realities.

The general focus of macroeconomic

discussion changed dramatically between the 1930s and the 1960s as the

focus changed from the time-discount component of the interest rate to

the inflation premium and from capital markets to labor markets. In summary

terms, Hayek's Prices and Production provided a capital-based account

of policy induced distortions in time discounts, while the macroeconomics

of the 1960s provided a labor-based account of policy-induced changes in

the inflation premium. The purpose here in making the contrast in this

way is not to pit one macroeconomic framework against the other (as in

done in Bellante and Garrison, 1988) but rather to point in the direction

of a third framework that may prove more applicable to the 1990s.

The third component of the

market rate of interest, the risk premium, has played a significant role

neither in Hayekian constructions nor in more modern ones. Typically, risk

premiums get mentioned only in introductory throat-clearing paragraphs

in which considerations of risks along with administrative charges and

other workaday matters are assumed away. At most, the perceived riskiness

of holding non-monetary assets helps in some formulations to explain the

demand for money. But there has been no macroeconomic theory attempting

to explain any episode of boom and bust in terms of the market's allocation

of risk-bearing or policy-induced distortions of risk-related market mechanisms.

Until recently, such a theoretical formulation would have little if any

application. But the macroeconomic experience of the 1980s and 1990s might

best be accounted for by just such a formulation.

The risk-based formulation

parallels Hayek's original triangulation and, to a lesser extent, the more

modern theorizing about short-run and long-run Phillips curves. In summary

terms, we can say that the market allocates risk-bearing among market participants

in accordance with the willingness of each to bear risk. Policies can create

a discrepancy between risk willingly born and risk actually born. Because

of a critical time element embedded in risk-bearing, such policies can

have cause-and-effect relationships that manifest themselves macroeconomically

as boom and bust.

The Economics of Risk Control and Risk Externalization

Not all conceivable policies that would interfere with the market's

allocation of risk-bearing would have significant macroeconomic effects.

Suppose, for example, that the legislature, which might take all market

rates of interest more than, say, five percent above the Treasury-bill

rate to reflect excessive riskiness, were to declare all payment for such

risk-bearing politically incorrect. A legislated Treasury-plus-five cap

on interest rates would have a direct and immediate effect on credit markets.

Entrepreneurs interested in relatively risky undertakings would face a

credit shortage. The effects of this partial prohibition against risk-taking

would differ little from the effects of a simple interest-rate cap. Black

and grey credit markets would emerge to partially offset the effects of

legislation, and the trade-off between debt and equity financing would

be biased in favor of equity. Apart from these effects, which are wholly

predictable on the basis of conventional microeconomics, there is no basis

for predicting that any macroeconomically significant consequences would

follow from such risk-control legislation.

The effects of this hypothetical

risk-control legislation are set out here in order to provide a basis for

contrasting those distortions of market mechanisms for allocating risk-bearing

that do have macroeconomically significant effects and those that do not.

The exposition also allows us to identify links between the economics of

risk allocation and the economics of credit allocation. We can anticipate

the argument by saying that, in terms of the macroeconomic significance

of the effects of intervention, credit control is to risk control what

credit expansion is to risk externalization. Legislative actions and policy

innovations may allow borrowers to take risks that are systematically out

of line with the risks perceived or actually born by lenders. So long as

risk is effectively concealed from lenders or actually shifted to others,

risk-taking will be excessive. The initial phase of excessive risk-taking

will manifest itself as an economic boom, but eventually, when actual losses

begin to change the perception of lenders and begin to impinge upon unsuspecting

others, the boom will give way to a bust.

Adding substance to this

summary account of boom and bust attributable to distortions of the risk

premium requires the identification of legislative action and policy innovation

that create a discrepancy between risk-taking and (perceived) risk-bearing.

The market process set into motion by the discrepancy can then be shown

to play itself out in the context of actual markets that embody risk-taking.

In this way, a capital-based account of legislative and policy-based distortions

in risk premiums can point to specific interventions that underlay the

boom of the 1980s and sowed the seeds for the bust—the Bush recession—in

the early 1990s

The single piece of legislation

most relevant to risk allocation in the 1980s' boom was the Depository

Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 (DIDMCA), which

dramatically changed the banking industry's ability and willingness to

finance risky undertakings. Increased competition within the banking industry

and from non-bank financial institutions drove commercial banks to alter

their lending policy so as to accept greater risks in order to achieve

higher yields. The deregulation gave new significance to the Federal Deposit

Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which continued to absolve the banks' depositors

of all worries about illiquidity and even about bankruptcy, while the Federal

Reserve in its long-established capacity of lender of last resort diminished

the banks' own concerns about such problems. The risks in the private sector,

then, were only partially reflected in higher borrowing costs and lower

share prices. In substantial measure, private-sector risks were transformed

into risks of inflation in the event of excessive last-resort lending by

the Federal Reserve and risks of a large and unbudgeted liability in the

event of excessive last-resort closings by the FDIC. But these risks were

born unknowingly and hence unwillingly by market participants and taxpayers

throughout the economy. During the 1980s, then, the increased riskiness

in the private sector was effectively externalized and diffused so that

the private-sector activity, spurred on by correspondingly increased yields,

was largely unattenuated by considerations of risk.

The policy innovation most

relevant to risk allocation in the 1980s' boom was the federal government's

dramatically increased reliance on deficit finance. The Federal Reserve

in its capacity to monetize government debt keeps the default-risk premium

off Treasury bills. This is not to say that the risk that would otherwise

attach itself to government securities is actually eliminated. The burden

of bearing risk is simply shifted from the holders of Treasury securities

to others. Borrowing and investing in the private sector is more risky

than it otherwise would be. Holders of private debt and equity shares must

concern themselves with all the usual risks and uncertainties of the market

place plus the risks and uncertainties attributable to potential changes

in the way the federal deficit is accommodated. The massive selling of

debt by the Treasury in foreign credit markets, in domestic credit markets,

or to the Federal Reserve can have major effects on the strength of export

markets, on domestic interest rates, and on the inflation rate. Inability

of market participants to anticipate the Treasury's borrowing strategy

translates into unanticipated changes in the value of private securities

and the real assets they represent. Speculative lending in the private

sector, such as for commercial real-estate development or for highly leveraged

financial reorganizations are risky in large part because of possible changes

in such things as the inflation rate, interest rate, trade flows, and tax

rates—the very things that can undergo substantial and unpredictable change

when the federal budget is dramatically out of balance (Garrison, 1993).

In circumstances where considerations

of risk figure importantly in accounting for the performance of the economy,

capital markets become the natural focus of attention. The focus on capital

is what makes the macroeconomics of the 1980s and 1990s more closely related

to Hayekian triangulation than to the labor-based short-run/long-run Phillips

curve analysis of the 1960s. Long-term, or capital-intensive, undertakings

are inherently more risky than short-term undertakings precisely because

more time must elapse before such undertakings can prove their profitability—more

time that increases the likelihood of some major change in deficit accommodation

or some attempt at deficit reduction that can turn expected profits into

losses.

The temporal segregation

of stages of production that make up the economy's capital structure puts

a dimension in the analysis that is absent in labor-based theorizing. There

is scope for profit-taking in early stages of production in cases where

ultimately the entire project—all stages considered—yields a substantial

loss. The possibility for short-term commitments in the early stages of

long-term projects coupled with the many imperfections in contingency markets

that allow for some hedging against changes in the federal government's

fiscal and monetary strategy warn against too literal an application of

the so-called efficient-market hypothesis. Ordinarily, markets allocate

both capital and labor efficiently—or at least more efficiently that any

alternative allocation mechanism. But a market system whose credit markets

involve risks that are partially concealed from the lender and partially

shifted to others will be biased in the direction of excessive risk-taking.

And excessive risks are converted in time into excessive losses.

Hayekian Triangles for the 1990s

Frequent but vague references in the financial and popular press to

the "excesses of the 1980s" can be taken to mean excess riskiness in comparison

to wealth holders' willingness to bear risk. The 1980s may best be understood,

then, as a decade in which risk externalization attributable to legislative

action and policy innovation gave rise to a substantial but ultimately

unsustainable economic boom.

This diagnosis of the macroeconomic

ills of the 1990s is more suggestive than conclusive. The purpose here

is to demonstrate the versatility of Hayekian theory rather than render

a final verdict on the most recent episode of boom and bust. Hayek gave

us a good start on capital-based macroeconomics. The insights wrapped up

in those triangles and the prospects for extension and application are

yet to be fully developed or fully appreciated.

References

Bellante, D. and Garrison, R.W. (1988) "Phillips Curves

and Hayekian Triangles: Two Perspectives on Monetary Dynamics," History

of Political Economy 20(2): 207-234.

Friedman, M. (1976) "Wage Determination and Unemployment,"

in M. Freidman, Price theory, Chicago: Aldine.

Garrison, R.W. (1993) "Public-Sector Deficits and Private-Sector

Performance," in L. White (ed.) The Crises in the Banking Industry,

New York: New York University Press.

Hayek, F.A. (1967) Prices and Production, 2nd

ed. New York: Augustus M. Kelley (first published in 1931, 2nd

ed. published in 1935, reprinted in 1967).

Hicks, J.R. (1965) Capital and Growth, Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

________. (1967) "the Hayek Story," in J.R. Hicks, Critical

Essays in Monetary Theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jevons, W.S. (1970) The Theory of Political Economy,

Harmondsworth: Penguin Books (first published in 1871).

Kaldor, N. (1942) "Professor Hayek and the Concertina

Effect," Economica 9: 359-382.

Keynes, J.M. (1931) "A Reply to Dr. Hayek," Economica

11: 387-397.

________. (1964) The General Theory of Employment,

Interest, and Money, New York: Harcourt, Brace and World (first published

in 1936).

Mises, L. von (1953) The Theory of Money and Credit,

New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press (first published in 1912).

Robbins, L. (1934) The Great Depression, London:

Macmillan.

Robinson, J. (1972) "The Second Crisis in Economic Theory,"

American

Economic Review 62, 2: 1-10.

Sraffa, P. (1932) "Dr. Hayek on Money and Capital," Economic

Journal 42: 42-53

|

Investment,

which entails the commitment of resources to a time-consuming production

process, adds to the time dimension of the economy's structure of production.

To allow for investment, consumption must fall initially in both nominal

and real terms. Once the capital restructuring is complete, the corresponding

level of consumption is higher in real terms than its initial level. The

nominal level of consumption spending, however, is lower than its initial

level because a greater proportion of total spending is devoted to the

maintenance of a more time-consuming production structure.

Investment,

which entails the commitment of resources to a time-consuming production

process, adds to the time dimension of the economy's structure of production.

To allow for investment, consumption must fall initially in both nominal

and real terms. Once the capital restructuring is complete, the corresponding

level of consumption is higher in real terms than its initial level. The

nominal level of consumption spending, however, is lower than its initial

level because a greater proportion of total spending is devoted to the

maintenance of a more time-consuming production structure.

of

production, (2) that the extent of the reduction diminishes as stages further

removed from consumption are considered, (3) that stages remote from consumption

experience an increased demand for input and (4) that stages of production

more remote than had existed before have been created anew. The slope of

the hypotenuse, now less steep than before, reflects a lower rate on interest

corresponding to the reduced time preference.

of

production, (2) that the extent of the reduction diminishes as stages further

removed from consumption are considered, (3) that stages remote from consumption

experience an increased demand for input and (4) that stages of production

more remote than had existed before have been created anew. The slope of

the hypotenuse, now less steep than before, reflects a lower rate on interest

corresponding to the reduced time preference.