Murray N. Rothbard: In Memorium

Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1995, pp. 13-18

Murray Rothbard (1926-1995)

Roger W. Garrison

In the late 1960s,

my interests were far removed from Austrian economics—and from any other

brand of economics, for that matter. I hadn't yet heard of Murray Rothbard

and thus couldn't even have imagined that I would be catapulted by him

into the midst of what would later be termed the "Austrian Revival." My

degree was in electrical engineering, but the hoped-for career was stillborn

because of Southeast Asia and the military draft. My years in uniform taught

me the importance of having a purpose by depriving me—temporarily—of the

possibility of having one. I did have time to read in the military, and

like many others in that period, I began reading Ayn Rand's novels as well

as her essays in moral philosophy. In the late 1960s,

my interests were far removed from Austrian economics—and from any other

brand of economics, for that matter. I hadn't yet heard of Murray Rothbard

and thus couldn't even have imagined that I would be catapulted by him

into the midst of what would later be termed the "Austrian Revival." My

degree was in electrical engineering, but the hoped-for career was stillborn

because of Southeast Asia and the military draft. My years in uniform taught

me the importance of having a purpose by depriving me—temporarily—of the

possibility of having one. I did have time to read in the military, and

like many others in that period, I began reading Ayn Rand's novels as well

as her essays in moral philosophy.

Objectivism is strong medicine,

especially for those like myself who had spent their college years avoiding

courses in the social sciences because of their apparent lack of structure

and reason. Rand's Capitalism: the Unknown Ideal was full of structure

and reason and provided a moral foundation for a free society. The Austrian

economists, featured in this book's recommended readings, would show just

what is—or ought to be—sitting on Rand's foundation. Austrian economics

is appealing to an engineering mind: basic principles, law-like propositions,

unequivocal conclusions—all grounded in logic and applicable to the world

as we know it. Authors that Rand believed to be worthy of attention are

listed in alphabetical order. I look back now at my yellowed paperback

purchased more than a quarter-century ago and note the neatly drawn check

marks that track the progress of my reading: books by Benjamin Anderson,

Lawrence Fertig, Henry Hazlitt, and Ludwig von Mises. Although my imperfect

memory tells me that Murray Rothbard's books were included in this list,

I see now that they are not. But Rothbard had been publishing for several

years and was for a time a member of Rand's inner circle. Any enthusiastic

reader would soon find his books.

I obtained a copy of America's

Great Depression through an inter-library loan. I found Rothbard's

account of boom and bust absolutely compelling and especially significant

in light of the stark contrast between the views of the Austrian economists

and those of the "educated" citizenry. With a monopoly on money creation,

the government could artificially cheapen credit and orchestrate a business

expansion, which eventually and inevitably would collapse. Policies commonly

defended in the name of stability and growth led instead to instability

and decay. In later years, I would attach even more significance to this

early book of Rothbard's as I discovered how badly other schools of economic

thought had botched their accounts of business cycles.

With the engineering market

glutted in the early 1970s when I and many of my peers were set free by

the military, a popular option was to work on an MBA degree. I chose to

pursue a masters in economics instead, thinking (erroneously) that the

MA would be as marketable and the coursework more interesting. I entered

the masters program at the University of Missouri at Kansas City. The courses

on macroeconomics offered a steady diet of Keynesian analysis in the conventional

form of interlocking diagrams that jointly determine the equilibrium values

for the economy's income and its interest rate. The substantial investment

involved in mastering the diagrammatical technique seemed to give professors

and students alike a special interest in defending Keynesian views.

In late 1972 I began to

devise an Austrian counterpart to the Keynesian diagrams. Rothbard's Man,

Economy, and State provided the primary source material. In the end,

I was able to draw together individual diagrams taken from or inspired

by Rothbard, Mises, Hayek, Böhm-Bawerk and Wicksell and show that

they all fit together into a coherent story about boom and bust. Titled

"Austrian Macroeconomics: A Diagrammatical Exposition," the paper was submitted

as partial fulfillment of the course requirements in macroeconomics. The

professor, whose preferred brand of economics was institutionalism as exposited

by Thorstein Veblen and Clarence Ayers, gave me a high mark on the paper

but confessed that he hadn't actually worked through the graphical analysis

and wasn't familiar with Austrian economics. To my surprise, though, he

offered to arrange for me to present the paper at the Midwest Economic

Association meetings to be held in Chicago in April 1973.

With some urging from this

professor, I agreed to go to Chicago. I soon realized, however, that neither

he nor anyone else had provided me with any critical feedback. No one,

in fact, had actually read the paper. And I was to present it to a professional

audience in April! The one action item that occurred to me was to mail

a copy of the paper to Murray Rothbard. Maybe he would respond in time

to give me some confidence about Chicago—or to allow me to renege on my

agreement to go.

About a week after mailing

the paper, I got a phone call—from Joey Rothbard. She introduced herself

with a very pleasant voice and said that her husband would like to speak

with me. I then listened for the voice of a learned professor but heard

instead an exceedingly jolly voice, interspersed with an infectious cackling

and irreverent asides about modern-day graduate programs. Rothbard was

clearly enthused about the diagrammatical exposition; he saw it as beating

the Keynesians at their own game. "Would you be coming to New York anytime

soon?" he asked. Although I had no plans whatever to go to New York, I

managed to announce: "I'll be there during spring break," at which point

he invited me for dinner and further discussion of the diagrams.

Dinner guests at the Rothbards'

are made to feel like special people. I was treated to a memorable dinner

with the warmest hospitality amid the book-lined walls of the Rothbards'

upper-westside apartment. After dinner more guests arrived: Walter Block,

Walter Grinder, and William Stewart, all of whom had carefully read my

paper. The discussion was lively, mostly positive, and full of good suggestions

for revision and further development. I took notes in the margins of my

own copy. The evening passed quickly, and I began to worry about overstaying

my welcome. But no one else seemed to be aware of the late hour. As midnight

neared, I began packing my papers away and thanking the Rothbards for an

unforgettable evening. The host and other guests seemed puzzled and almost

insulted by my tenuous movement in the direction of the front door. I did

not know that Murray was a complete and incurable night owl. For him the

evening had just begun. We had lots of discussion ahead of us including

some history and some methodology and quite a little bit of slightly gossipy

banter about people in the Libertarian/Austrian movement. As best I can

remember, I was allowed to leave around 4:00 a.m., after an invitation

was extended (and accepted) to attend a class later in the day at Brooklyn

Polytechnic Institute, where Murray taught economics to engineering students—and

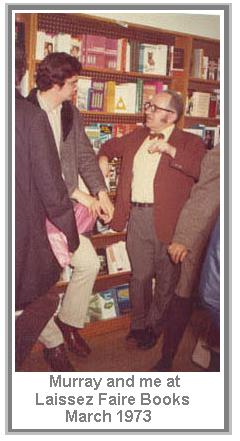

to stop by Laissez-Faire Books, where he would be autographing copies of

his just-released For a New Liberty (See photo). The evening had

crystallized into a major stepping stone in my own professional development.

But there was something else that had happened which now has a special

meaning for me. In the course of a single evening, Murray Rothbard, whose

name continued to signify eminence in economics, history, and philosophy,

had become for me just "Murray."

The presentation in Chicago was a virtual non-event, which, as I learned

later, is typical of sessions at professional meetings. But the disappointment

was overshadowed by the fact that Murray had invited me to attend a week-long

conference on twentieth-century American economic history sponsored by

the Institute for Humane Studies to be held in the summer at Cornell University.

He and Forrest McDonald were to lecture for a week to an audience consisting

mainly of student historians. As it turned out, I was one of only a few

economics students to attend. Near the end of the week, Murray asked me

to present my diagrammatics in an informal afternoon session. I foolishly

agreed. Since the audience of historians was largely unschooled in macroeconomics,

I felt I had to present first the mainstream Keynesian diagrammatics (which

typically takes a semester in undergraduate economics programs) and then

counter it with my own Austrian diagrammatics. Needless to say, the session

was a disaster. The audience, largely baffled, did include one economist,

who criticized me roundly at every turn. But I forgave Murray for asking

me to do the presentation and soon enough came to appreciate the criticisms

offered by the lone economist. She is to be thanked rather than forgiven.

The presentation in Chicago was a virtual non-event, which, as I learned

later, is typical of sessions at professional meetings. But the disappointment

was overshadowed by the fact that Murray had invited me to attend a week-long

conference on twentieth-century American economic history sponsored by

the Institute for Humane Studies to be held in the summer at Cornell University.

He and Forrest McDonald were to lecture for a week to an audience consisting

mainly of student historians. As it turned out, I was one of only a few

economics students to attend. Near the end of the week, Murray asked me

to present my diagrammatics in an informal afternoon session. I foolishly

agreed. Since the audience of historians was largely unschooled in macroeconomics,

I felt I had to present first the mainstream Keynesian diagrammatics (which

typically takes a semester in undergraduate economics programs) and then

counter it with my own Austrian diagrammatics. Needless to say, the session

was a disaster. The audience, largely baffled, did include one economist,

who criticized me roundly at every turn. But I forgave Murray for asking

me to do the presentation and soon enough came to appreciate the criticisms

offered by the lone economist. She is to be thanked rather than forgiven.

Although the week at Cornell

was rewarding in its own right, it benefited me mainly by putting me on

the invitation list for upcoming conferences in Austrian economics. The

following year (1974) was the South Royalton conference, a conference that

came to be widely recognized as the take-off point of the Austrian Revival.

There, Murray, teamed up this time with Israel Kirzner and Ludwig Lachmann,

gave stimulating lectures dealing with method, theory, and policy, all

published later on as The Foundations of Modern Austrian Economics,

edited by Ed Dolan. Henry Hazlitt and Bill Hutt added much insight and

perspective to the discussions. Milton Friedman was there for the opening

banquet. His now-famous remark that "there is no Austrian economics—only

good economics and bad economics" had a certain—but unintended—galvanizing

effect on conference. The list of listeners, most meeting one another for

the first time, now reads like a Who's Who in Austrian economics: Armentano,

Block, Ebeling, High, Lavoie, Moss, O'Driscoll, Rizzo, Salerno, Shenoy,

Vaughn. One purpose of the conference was to persuade Lachmann that there

was sufficient interest in Austrian economics to justify his coming out

of semi-retirement and teaching at New York University. By week's end,

the interest was not in doubt, and Lachmann soon began teaching at NYU.

For the two follow-on conferences

held in successive years, F. A. Hayek joined the original South Royalton

faculty. In 1975 the Austrians met at the University of Hartford in Connecticut;

in 1976 they met in England in Windsor Castle. At both conferences, papers

by South Royalton participants were presented and discussed. The Windsor

Castle papers, among which was my newly revised "Diagrammitical Expostition,"

were eventually published as New Directions in Austrian Economics,

edited by Lou Spadaro. This unique three-year sequence of conferences on

Austrian economics, engineered largely by Murray, nicely overlapped my

years in the graduate program at the University of Virginia, a school I

had chosen on Murray's recommendation.

I can easily say that Murray's

influence on my career has been so significant that I simply do not know

where I would be today or what I would be doing had it not been for his

guidance. I knew Murray for the last twenty-two years of his life. I look

back now and realize that he was not as old when I first dined with him

and Joey as I am now. In stature, though, he seemed to me then like the

Old Master—having more to show for his early years than most of us will

have in the longest lifetime. Since then, of course, his influence, both

personal and through his writing, has grown enormously. We owe much to

Murray for the fact that the years since South Royalton have seen a steady

growth of Austrian economics in universities both in the U.S. and abroad.

Beginning in 1976 there have been teaching conferences almost every year—at

Newark, DE, Oakland, CA, Boulder, CO, Milwaukee, WI, Auburn, AL, Palo Alto,

CA, Claremont, CA—sponsored first by the Institute for Humane Studies and

then by the Ludwig von Mises Institute. This year, the conference, billed

as the Mises University, will be held in Auburn and promises to be a most

significant event. Dedicated to the memory of Murray Rothbard, it will

feature more than two dozen faculty members lecturing on a wide range of

topics in economics, history, and philosophy.

Can Austrian economics survive

without Murray? Yes, it can and will survive and grow. Although his passing

leaves us all with an enduring sense of loss, we can see his life as the

virtual personification of dedication and purpose. His legacy will provide

us with the wisdom and the spirit to press on.

|