David Glasner, ed., Business Cycles and Depressions

New York: Garland Publishing Co., 1997, pp. 23-27

The Austrian Theory of the Business

Cycle

Roger W. Garrison

Grounded

in the economic theory set out in Carl Menger's

Principles of Economics

and built on the vision of a capital-using production process developed

in Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk's Capital and Interest, the Austrian

theory of the business cycle remains sufficiently distinct to justify its

national identification. But even in its earliest rendition in Ludwig von

Mises' Theory of Money and Credit and in subsequent exposition and

extension in F. A. Hayek's Prices and Production, the theory incorporated

important elements from Swedish and British economics. Knut Wicksell's

Interest

and Prices, which showed how prices respond to a discrepancy between

the bank rate and the real rate of interest, provided the basis for the

Austrian account of the misallocation of capital during the boom. The market

process that eventually reveals the intertemporal misallocation and turns

boom into bust resembles an analogous process described by the British

Currency School, in which international misallocations induced by credit

expansion are subsequently eliminated by changes in the terms of trade

and hence in specie flow. Grounded

in the economic theory set out in Carl Menger's

Principles of Economics

and built on the vision of a capital-using production process developed

in Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk's Capital and Interest, the Austrian

theory of the business cycle remains sufficiently distinct to justify its

national identification. But even in its earliest rendition in Ludwig von

Mises' Theory of Money and Credit and in subsequent exposition and

extension in F. A. Hayek's Prices and Production, the theory incorporated

important elements from Swedish and British economics. Knut Wicksell's

Interest

and Prices, which showed how prices respond to a discrepancy between

the bank rate and the real rate of interest, provided the basis for the

Austrian account of the misallocation of capital during the boom. The market

process that eventually reveals the intertemporal misallocation and turns

boom into bust resembles an analogous process described by the British

Currency School, in which international misallocations induced by credit

expansion are subsequently eliminated by changes in the terms of trade

and hence in specie flow.

The Austrian

theory of the business cycle emerges straightforwardly from a simple comparison

of a savings-induced boom, which is sustainable, with a credit-induced

boom, which is not. An increase in saving by households and a credit expansion

orchestrated by the central bank set into motion market processes whose

initial allocational effects on the economy's capital structure are similar

but whose ultimate consequences are sharply different.

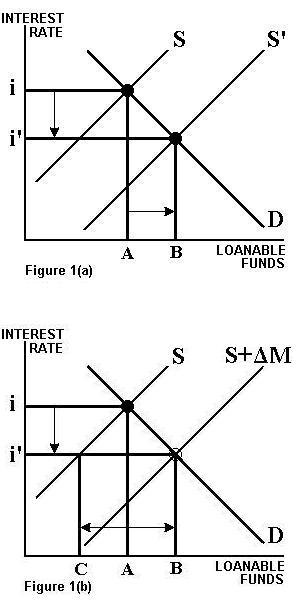

The general

thrust of the theory, though not the full argument, can be stated in terms

of the conventional macroeconomic aggregates of saving and investment.

The level of investment is determined by the supply of and demand for loanable

funds, as shown in Figures 1(a) and 1(b). Supply reflects the willingness

of households to save at various rates of interest; demand reflects the

willingness of businesses to borrow in order to finance investment projects.

Each figure represents a state of equilibrium in the loan market: the market-clearing

rate of interest is i, as shown on the vertical axis; the amount of income

saved and borrowed for investment purposes is A, as shown on the horizontal

axis.

An increase

in the supply of loanable funds, as shown in Figures 1(a) and 1(b) alike,

has obvious initial effects on the rate of interest and on the level of

investment borrowing. But the ultimate consequences differ importantly

depending upon whether the increased supply of loanable funds derives from

increased saving by households or from increased credit creation by the

central bank.

Figure

1(a) shows the market's reaction to an increased thriftiness by households,

as represented by a shift of the supply curve from S to S'.

Households have become more future-oriented; they prefer to shift consumption

from the present to the future. As a result of the increased availability

of loanable funds, the rate of interest falls from i to i', enticing businesses

to undertake investment projects previously considered unprofitable. At

the new lower market-clearing rate of interest, both saving and investment

increase by the amount AB. This increase in the economy's productive capacity

constitutes genuine growth.

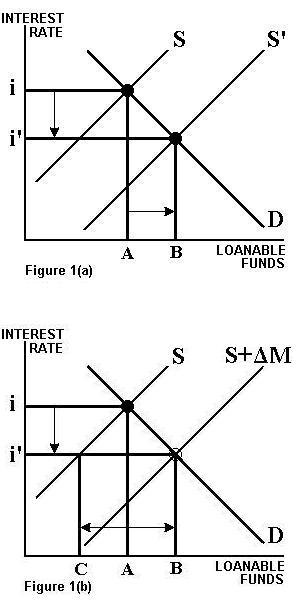

Figure

1(b) shows the effect of an increase in credit creation brought about by

the central bank, as represented by a shift of the supply curve from S

to

S+/\M. Households have

not become more thrifty or future-oriented;

the central bank has simply inflated the supply of loanable funds by injecting

new money into credit markets. As the market-clearing rate of interest

falls from i to i', businesses are enticed to increase investment by the

amount AB, while genuine saving actually falls by the amount AC. Padding

the supply of loanable funds with new money holds the interest rate artificially

low and drives a wedge between saving and investment. The low bank rate

of interest has stimulated temporary—rather than sustainable—growth. The

credit-induced artificial boom is inherently unsustainable and is followed

inevitably by a bust, as investment falls back into line with saving. Figure

1(b) shows the effect of an increase in credit creation brought about by

the central bank, as represented by a shift of the supply curve from S

to

S+/\M. Households have

not become more thrifty or future-oriented;

the central bank has simply inflated the supply of loanable funds by injecting

new money into credit markets. As the market-clearing rate of interest

falls from i to i', businesses are enticed to increase investment by the

amount AB, while genuine saving actually falls by the amount AC. Padding

the supply of loanable funds with new money holds the interest rate artificially

low and drives a wedge between saving and investment. The low bank rate

of interest has stimulated temporary—rather than sustainable—growth. The

credit-induced artificial boom is inherently unsustainable and is followed

inevitably by a bust, as investment falls back into line with saving.

Even in this

simple loanable-funds framework, many aspects of the Austrian theory of

the business cycle are evident. The natural rate of interest is the rate

that equates saving and investment. The bank rate diverges from the natural

rate as a result of credit expansion. When new money is injected into credit

markets, the injection effects, which the Austrian theorists emphasize

over price-level effects, take the form of too much investment. And actual

investment in excess of desired saving, CB, constitutes what Austrian theorists

call forced saving.

Other

significant aspects of the Austrian theory of the business cycle can be

identified only after the simple concept of investment reflected in Figures

1(a) and 1(b) is replaced by the Austrian vision of a multi-stage, time-consuming

production process. The rate of interest governs not only the level of

investment but also the allocation of resources within the investment sector.

The economy's intertemporal structure of production consists of investment

subaggregates, which are defined in terms of their temporal relationship

to the consumer goods they help to produce. Some stages of production,

such as research and development and resource extraction, are temporally

distant from the output of consumer goods. Other stages, such as wholesale

and retail operations, are temporally close to final goods in the hands

of consumers. As implied by standard calculations of discounted factor

values, interest-rate sensitivity increases with the temporal distance

of the investment subaggregate, or stage of production, from final consumption.

The interest

rate governs the intertemporal pattern of resource allocation. For an economy

to exhibit equilibrating tendencies over time, the intertemporal pattern

of resource allocation must adjust to changes in the intertemporal pattern

of consumption preferences. An increase in the rate of saving implies a

change in the preferred consumption pattern such that planned consumption

is shifted from the near future to the remote future. A savings-induced

decrease in the rate of interest favors investment over current consumption,

as shown in Figures 1(a) and 1(b). Further—and more significant in Austrian

theorizing—it favors investment in more durable over less durable capital

and in capital suited for temporally more remote rather than less remote

stages of production. These are the kinds of changes within the capital

structure that are necessary to shift output from the near future to the

more remote future in conformity with changing intertemporal consumption

preferences.

The shift

of capital away from final output—and hence the shift of output towards

the more remote future—can also be induced by credit creation. However,

the credit-induced decrease in the rate of interest engenders a disconformity

between intertemporal resource usage and intertemporal consumption preferences.

Market mechanisms that allocate resources within the capital structure

are imperfect enough to permit substantial intertemporal disequilibria,

but the market process that shifts output away from the near future when

savings preferences have not changed is bound to be ill-fated. The spending

pattern of income earners clashes with the production decisions that generated

their income. The intertemporal mismatch between earning and spending patterns

eventually turns boom into bust. More specifically, the artificially low

rate of interest that triggered the boom eventually gives way to a high

real rate of interest as overcommitted investors bid against one another

for increasingly scarce resources. The bust, which is simply the market's

recognition of the unsustainability of the boom, is followed by liquidation

and capital restructuring through which production activities are brought

back into conformity with consumption preferences.

Mainstream

macroeconomics bypasses all issues involving intertemporal capital structure

by positing a simple inverse relationship between aggregate (net) investment

and the interest rate. The investment aggregate is typically taken to be

interest-inelastic in the context of short-run macroeconomic theory and

policy prescription and interest-elastic in the context of long-run growth.

Further, the very simplicity of this formulation suggests that expectations—which

are formulated in the light of current and anticipated policy prescriptions—can

make or break policy effectiveness. The Austrian theory recognizes that

whatever the interest elasticity of the conventionally defined investment

aggregate, the impact of interest-rate movements on the structure of capital

is crucial to the maintenance of intertemporal equilibrium. Changes within

the capital structure may be significant even when the change in net investment

is not. And those structural changes can be equilibrating or disequilibrating

depending on whether they are savings-induced or credit-induced, or—more

generally—depending on whether they are preference-induced or policy-induced.

Further, the very complexity of the interplay between preferences and policy

within a multi-stage intertemporal capital structure suggests that market

participants cannot fully sort out and hedge against the effects of policy

on product and factor prices.

In mainstream

theory, a change in the conventionally defined investment aggregate not

accommodated by an increase in saving, commonly identified as overinvestment

and represented as CB in Figure 1(b), is often downplayed on both theoretical

and empirical grounds. In Austrian theory, the possibility of overinvestment

is recognized, but the central concern is with the more complex and insidious

malinvestment

(not represented at all in Figure 1(b) which involves the intertemporal

misallocation of resources within the capital structure.

Conventionally,

"reference cycles" are marked by changes in employment and in total output.

The Austrian theory suggests that the boom and bust are more meaningfully

identified with intertemporal misallocations of resources within the economy's

capital structure followed by liquidation and capital restructuring. Under

extreme assumptions about labor mobility, an economy could undergo a policy-induced

intertemporal distortion and its subsequent elimination with no change

in total employment. Actual market processes, however, involve adjustments

in both capital and labor markets that translate capital-market distortions

into labor-market fluctuations. During the artificial boom, when workers

are bid away from late stages of production into earlier stages, unemployment

is low; when the boom ends, workers are simply being released, and unemployment

rises.

Mainstream

theory distinguishes between broadly conceived structural unemployment

(a mismatch of job openings and job applicants) and cyclical unemployment

(a decrease in job openings). In the Austrian view, cyclical unemployment

is, at least initially, a particular kind of structural unemployment: the

credit-induced restructuring of capital has created too many jobs in the

early stages of production. A relatively high level of unemployment ushered

in by the bust involves workers whose subsequent employment prospects depend

on reversing the credit-induced capital restructuring.

The Austrian

theory allows for the possibility that while malinvested capital is being

liquidated and reabsorbed elsewhere in the economy's intertemporal capital

structure, unemployment can increase dramatically as reduced incomes and

reduced spending feed upon one another. The self-aggravating contraction

of economic activity was designated as a "secondary deflation" by the Austrians

to distinguish it from the structural maladjustment that, in their view,

is the primary problem. By contrast, mainstream theories, which ignore

the intertemporal capital structure, deal exclusively with the downward

spiral.

Questions

of policy and institutional reform are answered differently by Austrian

and mainstream economists because of the difference in focus as between

intertemporal distortions and downward spirals. The Austrians, who see

the intertemporal distortions as the more fundamental problem, recommend

monetary reform aimed at avoiding credit-induced booms. Hard money and

decentralized banking are key elements of the Austrian reform agenda. Mainstream

macroeconomists take structural problems (intertemporal or otherwise) to

be completely separate from the general problem of demand deficiency and

the periodic problem of downward spirals of demand and income. Their policy

prescriptions, which include fiscal and monetary stimulants aimed at maintaining

economic expansion, are seen by the Austrians as the primary source of

intertemporal distortions of the capital structure.

Although

the purging in the 1930s of capital theory from macroeconomics consigned

the Austrian theory of the business cycle to a minority view, a number

of economists working within the Austrian tradition continue the development

of capital-based macroeconomics.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bellante, Don and Roger W. Garrison. "Phillips Curves

and Hayekian Triangles: Two Perspectives on Monetary Dynamics," History

of Political Economy, vol. 20, no. 2 (summer), 1988, pp. 207-34.

Garrison, Roger W. "Austrian Capital Theory and the Future

of Macroeconomics," in Richard M. Ebeling, ed. Austrian Economics: Perspectives

on the Past and Prospects for the Future. Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale

College Press, 1991, pp. 303-24.

__________. "The Austrian Theory of the Business Cycle

in the Light of Modern Macroeconomics," Review of Austrian Economics,

vol. 3, 1989, pp. 3-29.

__________. "The Hayekian Trade Cycle Theory: A Reappraisal,"

Cato

Journal, vol. 6, no. 2 (Fall), 1986, pp. 437-53.

__________. "Time and Money: The Universals of Macroeconomic

Theorizing," Journal of Macroeconomics, vol. 6, no. 2 (Spring),

1984, pp. 197-213.

Hayek, Friedrich A. Prices and Production. 2nd

ed. New York: Augustus M. Kelley, Publishers, [1935] 1967.

Mises, Ludwig von. The Theory of Money and Credit

[originally published in German in 1912]. New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press, 1953.

Mises, Ludwig von et al. The Austrian Theory of the

Trade Cycle and Other Essays. Auburn, AL: The Ludwig von Mises Institute,

1983.

O'Driscoll, Gerald P. Jr. Economics as a Coordination

Problem: The Contribution of Friedrich A. Hayek. Kansas City: Sheed

Andrews and McMeel, Inc., 1977.

Robbins, Lionel. The Great Depression. London:

The MacMillan Co., 1934.

Rothbard, Murray N. America's Great Depression,

Third edition. Kansas City: Sheed and Ward, Inc., 1975.

Skousen, Mark. The Structure of Production. New

York: New York University Press, 1990.

|

Grounded

in the economic theory set out in Carl Menger's

Principles of Economics

and built on the vision of a capital-using production process developed

in Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk's Capital and Interest, the Austrian

theory of the business cycle remains sufficiently distinct to justify its

national identification. But even in its earliest rendition in Ludwig von

Mises' Theory of Money and Credit and in subsequent exposition and

extension in F. A. Hayek's Prices and Production, the theory incorporated

important elements from Swedish and British economics. Knut Wicksell's

Interest

and Prices, which showed how prices respond to a discrepancy between

the bank rate and the real rate of interest, provided the basis for the

Austrian account of the misallocation of capital during the boom. The market

process that eventually reveals the intertemporal misallocation and turns

boom into bust resembles an analogous process described by the British

Currency School, in which international misallocations induced by credit

expansion are subsequently eliminated by changes in the terms of trade

and hence in specie flow.

Grounded

in the economic theory set out in Carl Menger's

Principles of Economics

and built on the vision of a capital-using production process developed

in Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk's Capital and Interest, the Austrian

theory of the business cycle remains sufficiently distinct to justify its

national identification. But even in its earliest rendition in Ludwig von

Mises' Theory of Money and Credit and in subsequent exposition and

extension in F. A. Hayek's Prices and Production, the theory incorporated

important elements from Swedish and British economics. Knut Wicksell's

Interest

and Prices, which showed how prices respond to a discrepancy between

the bank rate and the real rate of interest, provided the basis for the

Austrian account of the misallocation of capital during the boom. The market

process that eventually reveals the intertemporal misallocation and turns

boom into bust resembles an analogous process described by the British

Currency School, in which international misallocations induced by credit

expansion are subsequently eliminated by changes in the terms of trade

and hence in specie flow.

Figure

1(b) shows the effect of an increase in credit creation brought about by

the central bank, as represented by a shift of the supply curve from S

to

S+/\M. Households have

not become more thrifty or future-oriented;

the central bank has simply inflated the supply of loanable funds by injecting

new money into credit markets. As the market-clearing rate of interest

falls from i to i', businesses are enticed to increase investment by the

amount AB, while genuine saving actually falls by the amount AC. Padding

the supply of loanable funds with new money holds the interest rate artificially

low and drives a wedge between saving and investment. The low bank rate

of interest has stimulated temporary—rather than sustainable—growth. The

credit-induced artificial boom is inherently unsustainable and is followed

inevitably by a bust, as investment falls back into line with saving.

Figure

1(b) shows the effect of an increase in credit creation brought about by

the central bank, as represented by a shift of the supply curve from S

to

S+/\M. Households have

not become more thrifty or future-oriented;

the central bank has simply inflated the supply of loanable funds by injecting

new money into credit markets. As the market-clearing rate of interest

falls from i to i', businesses are enticed to increase investment by the

amount AB, while genuine saving actually falls by the amount AC. Padding

the supply of loanable funds with new money holds the interest rate artificially

low and drives a wedge between saving and investment. The low bank rate

of interest has stimulated temporary—rather than sustainable—growth. The

credit-induced artificial boom is inherently unsustainable and is followed

inevitably by a bust, as investment falls back into line with saving.