Richard M. Ebeling, ed.

Economics Education: What Should We Learn About the Free Market?

Hillsdale: Hillsdale College Press, 1995, pp. 109-136.

The Persistence of Keynesian Myths:

A Report at Six Decades

Roger W. Garrison

The Keynesian

legacy is twofold. In the academic arena, Keynesian theory has caused professional

economists who are generally sympathetic to the ideal of a free society

to doubt that an unbridled market economy can bring us prosperity and stability.

In the political arena, Keynesian ideas have served as a justification

for bridling the market economy with fiscal and monetary policies. The

Full-Employment Act of 1946 and much subsequent legislation have allowed

policymakers to use the powers of taxing, spending, and money creation

in their attempts to achieve the prosperity and stability that is supposedly

out of the market's unassisted reach. Keynesian myths persist today largely

because of the uncritical presumption that the economy's sluggishness and

instability are to be attributed to fundamental defects in the market system

rather than to the perversities of the very policies intended to compensate

for those supposed defects. The Keynesian

legacy is twofold. In the academic arena, Keynesian theory has caused professional

economists who are generally sympathetic to the ideal of a free society

to doubt that an unbridled market economy can bring us prosperity and stability.

In the political arena, Keynesian ideas have served as a justification

for bridling the market economy with fiscal and monetary policies. The

Full-Employment Act of 1946 and much subsequent legislation have allowed

policymakers to use the powers of taxing, spending, and money creation

in their attempts to achieve the prosperity and stability that is supposedly

out of the market's unassisted reach. Keynesian myths persist today largely

because of the uncritical presumption that the economy's sluggishness and

instability are to be attributed to fundamental defects in the market system

rather than to the perversities of the very policies intended to compensate

for those supposed defects.

The preface to Keynes's

General

Theory begins with a warning: "This book is chiefly addressed to my

fellow economists."(1) Keynes goes on to

say, however, that "I hope it will be intelligible to others." Few economists

would share in Keynes's hope; his book would strain the imagination and

patience of even the most intelligent layman. Yet, dealing with Keynesian

myths requires that we delve into Keynes's book. Policies inspired by it

have affected us all; the layman has had to educate himself in economics

to understand just how. This article is chiefly addressed to that interested

layman. I can only hope that his tolerance for economic abstraction, interpretation,

and dispute will see him through it.

Robert Skidelsky has recently

published a 731-page volume entitled John Maynard Keynes, The

Economist as Savior: 1920-1937. This comprehensive look at Keynes's

middle years is the second volume of a three-volume biography. The first

volume, subtitled Hopes Betrayed: 1883-1920, was published eight

years ago.(2) There seems to be no worry

that reader interest might wane before the third volume, which will deal

with the final nine years of Keynes's life, appears sometime around the

turn of the century. John Maynard Keynes, who was born in the year of Karl

Marx's death (1883), shared a birthday with Adam Smith (June 5), and died

in 1946 on Easter Sunday, remains an enigma despite—or perhaps because

of—the unending attention to every detail of every aspect of his being.

Debate continues today about his economic vision—as Schumpeter used that

term—and about the policies and reforms implied by that vision as well

as many others proposed and defended in his name.

The unending controversy

about Keynes and his message is both fascinating and maddening. It is fascinating—almost

self-reinforcingly so—partly because of its endlessness. What did Keynes

actually have in mind when he wrote his General Theory? How, after

all these years, can there be such enduring scope for interpretation? And

in the absence of any consensus, why is his message, whatever it is, thought

to be a profound one? Trying to figure it all out can become an obsession.

Modern macroeconomists afflicted with a consuming interest in Keynes (I'll

admit to having a mild case of it) are not altogether different from the

modern devotees of Star Trek or the Andy Griffith Show. The one significant

difference, of course, is that neither the Trekkies nor the self-styled

Mayberrians have any impact on public policy. Unending debate about Keynes

is maddening because the continuing elusiveness of Keynes's message in

the academic arena is accompanied by a continuing reliance in the political

arena on macroeconomic policy prescribed and implemented on the basis of

Keynes's authority.

It is

not my intent simply to enumerate the propositions that could justifiably

be described as Keynesian myths and offer reasons for the persistence of

each one. As will be argued later, such a myth-at-a-time approach may be

unproductive. Instead, I take my cue from a book just half as old as Keynes's:

Keynes'

General Theory: Reports of Three Decades, edited by Robert Lekachman.(3)

Many a student of my generation, including myself, got started down the

road toward some understanding of Keynes by reading the essays in this

volume. I now offer an essay of my own that might be appropriate, should

some devotee be up to the task, for the sequel: Reports at Six Decades—and

Counting.

Interpreting Keynes

The practice among Keynes's interpreters of attempting

to combine their own wisdom with the authority of Keynes has become commonplace.

After offering his own interpretation of a particular point, Lawrence Klein

concluded that "...Keynes did not really understand what he had written."

(4)

Joan Robinson once remarked that "there were moments when we had some trouble

getting Maynard to see what the point of his revolution really was." (5)

Anatol Murad presumptuously entitled his own book What Keynes Means.

(6)

These and many other interpreters are guilty of writing about what Keynes

meant, what Keynes must have had in the back of his mind, what Keynes should

have said, or how Keynes would have changed his mind—if only he had lived

a few years longer. According to Alan Coddington, Robert Clower is guilty

of "reading not so much between the lines as off the edge of the page."

(7)

Some three decades after Keynes published his most influential book, Clower

offered an interpretation that, although revealing about the workings of

a market economy, was not very true to the scripture. It stood in contradiction

to some of the most clearly written passages. Nonetheless, Clower asserted

that either this is what Keynes had "at the back of his mind, or most of

the General Theory is theoretical nonsense." (8)

Axel Leijonhufvud's interpretation

more nearly resembles the views

of one of Keynes's predecessors (Knut Wicksell) and one of his ablest critics

(William H. Hutt), but Leijonhufvud's

assessment of

the business of interpreting Keynes is on the mark: "The impression

of Keynes that one gains from [reading his interpreters] is that of a Delphic

oracle, half hidden in billowing fumes, mouthing earth-shattering profundities

whilst in a senseless trance—an oracle revered for his powers, to be sure,

but not worthy of the same respect as that accorded the High Priests whose

function it is to interpret the revelations." (9)

Well-credentialed scholars

can be found on both sides of every issue: Is the General Theory

a continuation of the work begun in Keynes's Treatise on Money,

or is it a revolutionary break from his earlier book? Is the assumption

of fixed or sticky prices and wages critical to Keynes's arguments, or

is it merely a convenient means of making those arguments? Does

the so-called liquidity trap, which prevents a falling wage rate from reducing

unemployment and renders monetary policy impotent, figure importantly in

Keynes's case for fiscal activism, or is it only a curious extreme with

no historical or practical importance? Does Keynes actually contend that

the economy can be suffering from widespread unemployment and nonetheless

be in equilibrium, or is he saying that market adjustments in circumstances

of economywide disequilibrium may need to be augmented with or supplanted

by policy prescription? Is the standard textbook rendition of Keynesianism,

which largely abstracts from problems of uncertainty, faithful to Keynes's

theory, or is the notion that capital markets are debilitated by pervasive

uncertainty an important part of his central message? Finally, was it Keynes's

intention to condemn capitalism or to provide us with the appropriate policy

tools to keep it in repair?

One difficulty

in getting a clear reading of Keynes on these and other issues stems from

his mixing of levels of abstraction. He intermingles institutional considerations,

historical givens, and abstract expressions: The wage rate, which is determined

by labor unions (largely? wholly?), is an historical given; the resulting

aggregate supply is "Z(N)," an abstract and somewhat cryptic

function of the level of employment. At some points, Keynes is condescendingly

cryptic. When faced with the question of whether monetary expansion could

trigger an artificial boom, Keynes borrows some imagery from Ibsen and

writes: "at this point, we are in deep water. 'The wild duck has dived

down to the bottom—as deep as she can get—and bitten fast hold of the weed

and tangle and all the rubbish that is down there, and it would need an

extraordinarily clever dog to dive down and fish her up again'" (p. 183).

Leijonhufvud takes this passage to be an obvious slap at F. A. Hayek's

treatment of forced savings: "But here Keynes is ... a dead duck in shallow

water"—meaning that he was dead wrong about Hayek, owing to the shallowness

of his own understanding of Austrian capital theory. (10)

Keynes also intermingles

the issues of theory, policy, and reform. How does the capitalist system

work? Why does it sometimes—or generally—not work so

well? How can it be made to work better? And what alternative system might

be preferable? Attempts by interpreters to answer these questions selectively

have given rise to Keynesian Hydraulics, Keynesian Kaleidics, and what

I have called Keynesian Splenetics. These three interpretations are interrelated

on the basis of their addressing different combinations of the questions:

(1) John Hicks and Alvin Hansen are responsible for the Hydraulics of modern

textbooks. A set of interlocking graphs, representing the real and monetary

sectors of the economy, determine equilibrium levels of aggregate income

and the interest rate and serve as the basis for prescribing combinations

of fiscal and monetary policies that will achieve some income/interest-rate

goal.(11) (2) G. L. S. Shackle criticized

this overly mechanistic view with his own Keynes-inspired Kaleidics: two

of the graphs in the Hicks-Hansen model, namely the demand for investment

funds and the demand for liquidity, are virtually unanchored in economic

reality and are prone to sudden and dramatic change. The successive patterns

of demand are no more predictable, in the judgement of Shackle's Keynes,

than the successive patterns of shapes and colors seen through a kaleidoscope.(12)

(3) Fiscal and monetary tools, then, are of questionable use and, at best,

give us an interim fix. With prospects dim for meaningful and lasting improvement

in the market economy's performance, the ultimate solution is to replace

our depression-prone capitalism with something more stable. Needed reform

is radical in nature but can be introduced gradually. It will involve "depriving

capital of its scarcity value," "the euthanasia of the rentier," and a

"comprehensive socialisation of investment" (pp. 376-78). When Keynes writes

of the prospects for such reform and hence for eliminating what he considers

to be the more offensive aspects of capitalism, he adopts a distinctive

spleen-venting tone, and hence: Keynesian Splenetics. (13)

Adding

still another dimension to the business of interpreting Keynes is the fact

that the lens through which the critics and interpreters peer is a zoom

lens. Henry Hazlitt zoomed in to give us the ultimate close-up—or so it

must have seemed at the time—by dealing with Keynes's masterpiece on a

virtual page-by-page basis. The propositions so gleaned from the General

Theory are neither jointly supportable nor even mutually reinforcing.

According to Hazlitt's reading, for instance, saving and investment are

(i) two names for the same thing and (ii) cause trouble when they diverge.

(14)

Interpreters more sympathetic than Hazlitt have tended to zoom back and

look at the big picture. At a distance Keynes's verbiage flows together

into an extraordinarily fertile inkblot; the lens becomes more like a mirror.

Many a macroeconomist has dreamed up an idea only to see it right there

in the General Theory on a subsequent rereading. Sidney Weintraub,

a leading Post-Keynesian, initially claimed authorship of the notion of

mark-up pricing but latter attributed this stockboy's view of the pricing

process to Keynes. (15)

A final

understanding of Keynes's message has emerged neither from a page-at-a-time

reading nor from an inkblot-at-a-time musing. So, in a seeming exercise

of one-upmanship, Fred Glahe has given us a word-at-a-time rendition of

Keynes's book. Working with a digital scanner and word processor, Glahe

produced a concordance of the General Theory. (16)

Each and every word Keynes used is listed in alphabetical order together

with the word count plus page and paragraph references. We learn, for instance,

that Keynes used the word "capitalism" four times but "socialism" only

twice; "optimism" six times but "pessimism" only twice. Keynes wrote "always"

52 times, "sometimes" 30 times, and "never" only 18 times. What future

interpreters will make of all this remains to be seen. I suspect that the

very existence of a concordance says more about Keynes and his interpreters

than even the most inspired use of it can reveal about Keynes's intended

message.

Even

the title of the General Theory has been a source of dispute. Old

debate centered on the full title, The General Theory of Employment,

Interest, and Money. Textbook discussions that pit Keynesianism against

Monetarism sometimes distinguish these two schools on the basis of a key

question about the relevance of changes in the quantity of money: Does

money matter? The conventional account—in which Monetarists say "yes" while

Keynesians say "no"—is hard to reconcile with the fact that Keynes included

"Money" in his title. A more revealing debate concerns the short title.

Is "general" to be contrasted with "special," as indicated in the single

paragraph that makes up the book's first chapter? Or is "general" to be

contrasted with "partial," as suggested by Keynes's rejection of simple

supply-and-demand analysis and his emphasis on the interdependencies among

markets for goods and for labor? Does the appearance of the word "theory"

or the omission of the word "policy" carry its own message?

Some

seem to believe that Keynes's book is fundamentally unconcerned with policy

and reform; others believe that the book is, despite its title, a tract

for the times. As careful a scholar as Don Patinkin has recently admonished

one of his fellow interpreters for dwelling on the issues of policy or

reform: the General Theory, after all, is a book about theory,

as advertised in its title. (17) On a Glahe-based

reckoning, Patinkin is 74.4 percent correct. Including the plural and possessive

variants of the words, Keynes wrote "theory" 236 times and "policy" only

81 times. But we can award very little partial credit here. After all,

Keynes used the word "euthanasia" only three times (all three on p. 376),

but he used it where it counts. Suppose a veterinarian examines your aging

horse and writes a comprehensive report consisting of two parts. The first

part is a long and ponderous explanation of what all is wrong with your

horse, why you shouldn't expect him to recuperate on his own, and how an

enlightened application of veterinary medicine could yield some marginal

improvement in his condition. The second part is a short conclusion, in

which he recommends that your horse be put to sleep. Now, which part of

this report is the most "important," and what is its "central" message?

The veterinarian used the word "sleep" only once. According to Patinkin,

Keynes's last chapter (where euthanasia appears as an action item) "could

have been omitted without affecting [Keynes's] central message.... Chapter

24 (together with the other chapters that make up his Book VI) is essentially

an appendage to the General Theory, and one should not let the appendage

to a text wag its body." (18)

A more

recent and more telling reading of Keynes's title is Skidelsky's. Albert

Einstein published his "General Theory of Relativity" in 1915. Keynes was

self-consciously and self-confidently posturing as Einstein's counterpart

in economics. "Keynes's identification with Einstein," according to Skidelsky,

"is ... too clear to miss." (19) And the

impression he intended to create is the obvious one: Keynes is to Marshall

what Einstein is to Newton. A. C. Pigou, successor to Marshall, noted early

on that "Einstein actually did for Physics what Mr Keynes believes himself

to have done for Economics."(20) James

K. Galbraith draws from Keynes's rhetoric to detail the parallels between

the two general theories—of relativity and of employment. For example,

"[t]he Classical theorists resemble Euclidean geometers in a non-Euclidean

world who, discovering that in experience straight lines apparently parallel

often meet, rebuke the lines for not keeping straight—as the only remedy

for the unfortunate collisions which are occurring. Yet, in truth, there

is no remedy except to throw over the axiom of parallels and work out a

non-Euclidean geometry. Something similar is required in economics" (p.

16).(21) On this Skidelsky/Galbraith reckoning,

the title tells us more about the Delphic oracle's view of himself than

about what the High Priests can actually find in his book.

Judging by the Standard of Generality

Self-consciously created or not, the notion of Keynesian/Einsteinian

parallels is not an indictment of Keynesian macroeconomics. Devising a

more general theory, in economics as in physics, is a worthy undertaking.

But Keynes's General Theory is put in its worst light precisely

when judged by the standard of generality. If ever there was a special

theory, applicable only in the short run and under highly restrictive conditions,

it is his. Worse, the implementation of Keynesian policy works to make

the short run shorter and the restrictive conditions less likely to prevail.

And still worse, Keynesian fiscal and monetary activism interferes with

the self-correcting forces in the market economy, causing the economy to

be less efficient, less stable, and more depression-prone than it otherwise

would be. Perversely, the resulting unemployment of labor and other resources

and the discoordination in financial markets become the basis for advocating

the continuance of policy activism. In an ill-conceived effort to stabilize

the economy, policy activism has Keynesianized the economy; the

unintended consequences of the Keynesian medicine have helped give presistence

to the myths about the nature of the malady. These indictments of Keynesianism

derive from the policy analysis of several modern strands of market-oriented

macroeconomics.

The most

telling restrictive assumptions in the General Theory are those

that create a hard link between the employment of labor and total income

in the economy. The common practice of theorizing in terms of aggregate

income but stating conclusions in terms of employment has become so ingrained

that the hard link is simply taken for granted. Entrenched analytical convention

has a way of dulling our awareness of the problems it skirts. Any theory

claiming to be general, however, must soften this hard link. While a change

in total income might reflect a change in the overall employment of labor,

it might reflect instead a change in the value of labor or a change in

the mix of skilled and unskilled labor or a change in the value or quantity

of some other productive input. Following typical textbook presentations,

total income (Y), for an economy in equilibrium, is given by the

sum of three products: Y = RL + WN + iK, where

L, N, and K are the classical factors of production (land,

labor and capital), and the coefficients R, W, and i

are the respective prices (the rental rate, wage rate, and interest rate).

For an economy out of equilibrium, we would also have to include a fourth

term to represent entrepreneurial profit. To be consistent with the basic

Keynesian vision, an increase in income of, say, ten percent must imply

an increase in the employment of labor of ten percent plus corresponding

increases in the employment of both land and capital. That is, all macroeconomically

relevant changes are unidirectional changes in resource utilization and

affect only the scale of operation for the economy as a whole. Keynes explicitly

assumes (in his often-overlooked Chapter 4) a fixed structure of industry,

which precludes relative movements in factor incomes. (22)

He even assumes a fixed mix of labor skills and thereby precludes the possibility

that an increase in skilled relative to unskilled workers might increase

the effective labor input while the actual number of workers remains unchanged

or even decreases. An increased N, then, always means more workers

employed. This same structural straitjacket, incidentally, is also worn

by Keynes's aggregate supply function, Z(N), mentioned earlier.

The hard

link between N and Y (and between N and Z)

blinds us to the economy's ability to adapt to all sorts of relative changes

in market conditions and even imposes limits to changes in the economywide

scale of operation. "Bottlenecks," as Keynes called them (pp. 300-301 and

passim),

may develop in some sectors of the economy, preventing the economy as a

whole from actually reaching a position of full employment and igniting

inflation while unemployment still persists. These bottlenecks have their

counterpart in modern textbooks as the (rounded) elbows that characterize

the backwards-L aggregate supply curves. They mark the point (or region)

where quantity adjustments give way to price adjustments. In a biting footnote,

Hayek discussed Keynesian bottlenecks (and corresponding elbows) in the

light of Marshallian supply curves: "I should have thought that the abandonment

of the sharp distinction between the 'freely produced goods' and the 'goods

of absolute scarcity' and the substitution for this distinction of the

concept of varying degrees of scarcity (according to the increasing costs

of reproduction) was one of the major advances of modern economics. But

Mr. Keynes evidently wishes us to return to the older way of thinking.

This at any rate seems to be what his use of the concept of 'bottlenecks'

means; a concept which seems to me to belong essentially to a naive early

stage of economic thinking and the introduction of which into economic

theory can hardly be regarded as an improvement."(23)

The nature

of changes in the economy's total income is further restricted by assumptions

about the movements in wages and prices. Much of the General Theory

makes use of the simplifying assumption that both the wage rate and the

price level are fixed. Any increase in income, then, is sure to be a real

increase rather than only an increase in its nominal, or dollar, value.

Interpreters are correct, however, in arguing that fixed or sticky wages

are not central to Keynes's theory. Prices and wages that are flexible—even

perfectly flexible—do come into play. But Keynes sees the wage rate and

the price level as always moving together such that the real wage

rate is unaffected. He hedges his bets by claiming, for instance, that

(even in the classical view) changes in the nominal wage rate cause prices

to change almost in the same proportion leaving the real wage and

the level of employment practically unchanged (paraphrased from

p. 12). One might think that when the hedges are dropped, all bets are

off. But it isn't so. Bottlenecks and relative movements in prices and

wages aside, all changes in demand, when the economy is operating below

potential (and Keynes believed that it generally is), are taken to imply

proportionate changes in employment. Whether the nominal wage rate and

the price level are separately fixed or jointly variable, the real wage

rate, defined simply as the nominal rate adjusted for price-level changes,

is forever constant. Critics are entitled to wonder how the real wage ever

got to be what it is. The explanation would have to lie outside of Keynesian

macroeconomics, for Keynes offered no special theory of the real wage rate

and certainly no general theory of it that subsumed the allegedly special

classical case.

Sins of commission

get compounded by sins of omission. Special attention to the time element

was essential, in Keynes's view, in making the leap from the classical

vision to his own. But the many direct references to the time dimension

as well as numerous indirect references involving the uncertainty of the

future, the importance of expectations, and the volatility of long-term

asset prices contribute more to the book's tone than to the force of its

argument. Any explanation of the actual market process that allocates resources

over time—whether that process is believed to work well or to work poorly—must

draw heavily from capital theory. But capital theory, which deals with

the intertemporal pattern of resource allocation within the investment

sector, was no part of Keynes's attempted move toward generality. Further,

the rate of interest, which was widely believed to govern the allocation

of resources both within the investment sector and between consumption

and investment, was given alternative duty by Keynes, namely equilibrating

the market for liquidity. On the key issue of the intertemporal allocation

of resources, it did not even matter that there was no interest rate available

to do the job; there was, in fact, no job to be done. The assumption of

structural fixity precluded most all of the allocative processes that capital

theory illuminates. It is worth noting here that a more legitimate claim

to having achieved generality could have been made by Keynes's arch rival

Hayek, who had already begun to build a capital-based macroeconomics and

to identify those circumstances under which the market mechanism for allocating

intertemporally worked well and those under which it worked poorly.(24)

How could Keynes

expect to arrive at more general conclusions—or any conclusions at all—with

such an assumption-encumbered, hedged, and capital-free theory? The key,

it turns out, was expectations, which could turn the argument one way or

the other depending on where it needed to go. Expectations served Keynes

as something of a wild card, a get-out-of-jail card, a license for theoretical

free-wheeling. Falling prices can send demand up or down depending on whether

they are expected to keep falling or to rebound. A low rate of interest

may or may not persist depending on whether it is taken to be an abnormally

low rate or expected to become a new normal rate. Changes in the terms

of trade could be exacerbating or ameliorating depending on which would

better fit Keynes's immediate purpose. Allan Meltzer justifiably faults

Keynes for his cavalier treatment of expectations. (25)

Adopting

restrictive assumptions that highlight unidirectional and lockstep changes

in resource utilization to the exclusion of all relative changes and positing

abrupt discontinuities in supply curves are the makings of a very special—and

especially implausible—theory. Imposing similar restrictions on price changes

relative to wage changes and omitting all scope for adjustments in the

capital structure pushes Keynes's theory even further in this direction.

It is difficult to conceive of structural fixity and bottlenecks as important

aspects of some truly general theory for which classical economics is a

special case.

The generality

achieved by Einstein is reflected in his equations by their inclusion of

the Lorentz factor (1 - v2/c2)-1/2,

where v is the velocity of the object under study and c is

the speed of light. For speeds of bowling balls, cannon balls, and much

else, this factor differs insiginificantly from unity and the conclusions

of Einstein's more general theory are the same as those of Newton's special

theory. (Note, though, that Newton's so-called special theory is the relevant

theory in all cases except those in which the speeds under investigation

are close to the speed of light.) Keynes hints at an analogous relationship

between his general theory and classical theory: If our policies "succeed

in establishing an aggregate volume of output corresponding to full employment

... the classical theory comes into its own again from this point onwards"

(p. 378). But despite this rhetoric, there is no Lorentz factor at work

here that identifies classical theory (which features relative movements

of both prices and quantities in the face of scarcity) as a special case

of Keynesian theory (which deals only with the economy's overall scale

of operation in conditions of economywide resource idleness). Quite to

the contrary, the implied analogy between the speed of light and full employment

weighs against Keynes perspective on his own theory: as objects approach

the speed of light and as the economy approaches full employment, considerations

of relativity and of scarcity give preeminence to Einstein over Newton

and to Marshall over Keynes.

In the

light of the Keynesian/Einsteinian parallels, we see that Keynes's intent

was to make a classical economist who applies supply and demand analysis

to the markets for goods, labor, and loanable funds look as foolish as

a Newtonian physicist who chases moonbeams in hopes of getting a fix on

the speed of light. Keynes actual accomplishment, however, fell short of

his intent. He succeeded only in showing how many assumptions, hedges,

and omissions were necessary to force-fit economic theory into his own

vision of capitalist society. Obvious as it now seems, the idea that Keynes

thought he was Einstein has been recognized by only a few scholars—and

mostly by those who would count themselves as admirers of Keynes. Thus,

the General Theory has not been critically judged by the standard

that this view of its author entails.

Posing a Critical Question

Quite independent of what Keynes actually wrote

in his General Theory and what interpreters have taken him to mean,

there is a critical question that can be posed using the Keynesian macroeconomic

magnitudes (consumption and investment)—a question that would draw a broad

spectrum of answers from even the most reasonable and well-intentioned

economists. We can frame this question in terms of the familiar production

possibilities frontier, which always gets some play in the introductory

chapters of principles-level textbooks but has yet to become an integral

part of macroeconomic analysis. (26) The

frontier emphasizes the fact of economic scarcity by showing the various

combinations of consumer goods and investment goods that can be produced

given the constraints imposed by resource availabilities and the state

of technology. (SEE INSERT.) For any point on the

frontier, the economy's labor force is fully employed; unemployment (Keynes

would attach the adjective "involuntary") is implied by any point inside

the frontier. We begin with a wholly private, fully employed economy producing

some particular combination of consumption and investment goods that reflects

the saving preferences of market participants. The economy is in equilibrium

in both the Marshallian sense (market-clearing prices prevail all around)

and in the Keynesian sense (all income earned gets spent either by consumers

or by investors).

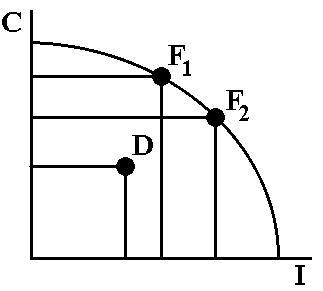

THE PRODUCTION POSSIBILITIES

FRONTIER

The production possibilities

frontier depicts a fundamental trade-off that governs resource usage. The

economy's resources can be employed partly in the production of consumer

goods (C) and partly in the production of investment goods (I). The investment

goods will  add

to the stock of capital, increasing the economy's capacity for producing

both categories of goods in the future. add

to the stock of capital, increasing the economy's capacity for producing

both categories of goods in the future.

In a fully employed economy, the particular combination of consumer goods

and investment goods actually produced will be represented by a point

somewhere on the frontier, such as F1. In a depressed economy, the

production of consumption and investment goods is accompanied by a widespread

idleness of labor and other resources. Depression is represented by a point

inside the frontier, such as D.

A well-functioning market not only keeps the economy on the frontier but

also allocates the resources between consumption and investment in accordance

with the saving preferences, or time preferences, of market participants.

The

more saved, the more invested, and the faster the frontier itself expands

outward.

Saving preferences can change. Suppose, for instance, that consumers become

more thrifty. They choose to forego current consumption so as to be able

to enjoy higher levels of consumption in the future. The allocation of

labor and other resources must be changed accordingly: the economy has

to move from F1 to F2, where the production of consumer goods is reduced,

and the resources thus freed up are used to increase the economy's productive

capacity.

The critical question that separates market-oriented economists from Keynesians

is: Will the market get us from F1 to F2 in response to an increase in

thrift? Austrians, (as well as Classicists and Monetarists) say "yes";

Keynesians say "no." The Keynesians believe that a saving-induced movement

away from F1 will result in unemployment as represented by D and that policy

activism is required to return the economy to the frontier. The Austrians

believe that a saving-induced movement away from F1 can take us to F2 but

that government policy aimed at forcing the economy toward F2 (i.e. artificially

cheap credit, which stimulates investment) will be self-defeating and will

send the economy inside the frontier before the market eventually returns

it to F1. That is, genuine saving begets growth; forced saving begets depression.

Now suppose

that income earners want to save more of their incomes in order to enjoy

even higher levels of consumption in the future. This preference change

requires a movement along the frontier in the direction of more investment

(and at the expense of consumption). Is there a market mechanism that can

get the economy from the first point to the second in response to such

a preference change? This is the critical question. We can imagine a movement

from one point on the frontier to the other along a path that dips below

the frontier. Although allowing for some transitory unemployment biases

the question in favor of a Keynesian answer, it crystallizes the issue

that separates macroeconomists into Keynesian and non-Keynesian camps.

Consumers,

by reducing their consumption spending, that is, by saving, have caused

an initial reduction in economic activity, as represented by some point

inside the frontier. Will the market forces set into motion by this increased

saving steer the economy back to the frontier or drive it deeper into the

interior? An adjustment path that drops below the frontier implies that

market signals are mixed: decreased consumption means excess inventories,

which signal producers to cut back until inventories stabilize at desired

levels; increased saving means favorable credit conditions and a low rate

of interest, which signal producers to expand capacity.

Keynes's

assumption of a fixed structure of industry would not allow for high inventories

and low interest rates to have their separate effects. They simply push

the business community in opposite directions, and the stronger of the

two wins out. Keynes claimed, in effect, that the forces exacerbating the

savings-induced idleness would dominate. The grim reality of the Great

Depression, he believed, had eliminated all doubt about the matter. He

chided his predecessors and contemporaries for believing otherwise and

insisted that there is no nexus in the market economy which translates

decisions to save into decisions to invest (p. 21).

By contrast,

Austrian macroeconomics, which was built on a theory of the capital structure,

could and did allow for the two separate effects. And in the context of

a time-consuming and adjustable structure of production, the two effects

were seen as mutually reinforcing rather than diametrically opposing. That

is, current production is reduced, bringing inventories back into line

and freeing up resources that can be used to expand productive capacity,

which will allow for increased future production. This intertemporal reallocation

of resources away from the present and toward the future is wholly consistent

with the initiating change in preferences. The labor force is once again

fully employed; the new higher level of investment (made possible by the

increased saving) allows for a higher rate of economic growth and hence

greater levels of consumption in the future.(27)

Which

of the two views, Austrian or Keynesian, more accurately portrays market

economies? A price system working at its best would reallocate resources

from consumer-goods industries to investment-goods industries without the

economy suffering even the transitory unemployment that we have assumed

occurs. Workers would be bid away from one industry directly into another

rather than be absorbed into the expanding industry some time after being

released from the contracting one. If the economy is moved along the frontier

rather than through its interior, there is no ambiguity in the market signals,

no temporary slack that might set the market off on the wrong track. But

this is only to say that if the market works well, it works very well.

An analogous

argument can demonstrate that if the market works badly, it works very

badly. Temporary slack may be clearly evident as the demand for consumer

goods shifts from the present into the future. Further, the increase in

demand in the future has no direct and concrete way of showing itself in

the present. And if the weaknesses in present market conditions begin to

win out over the anticipated strength of future market conditions, that

strength will never get a chance to show itself. An increasing rate of

unemployment will further weaken consumer demand, and worse, investors

taking their cues from current market conditions are likely to abandon

all plans to expand capacity. The economy will simply sink into a depression.

The idea that savings brings on depression is, of course, Keynes's "paradox

of thrift."

The intertemporal

relationship between current investment goods and future consumption goods

is the focus of capital theory—a theory that undergirds the macroeconomics

of the Austrian school but that was very much lacking in Keynes's General

Theory. In the absence of a future consumer demand that shows itself

in some direct and objective way, macroeconomists must focus on indirect

and subjective ways that such future demand might come into play. The indirect

markets for future consumption goods are nothing but the present markets

for labor and other resources that enter into the production for the future.

Future demand manifests itself in the present in the form of entrepreneurial

expectations. Keynes cut hopes short by assuming perverse expectations

(low present demand means low future demand), while the Austrians kept

hope alive by allowing for the possibility of expectations that are consistent

with consumer preferences. Recognizing that the outcome depends critically

upon the success or failure of entrepreneurship, the Austrians investigate

alternative institutional arrangements under which the free play of expectations

may inhibit or foster the translating of savings into investment.

This

way of putting things—posing the critical question—draws heavily on the

market's ability (or inability) to coordinate intertemporally. While the

denial that the market translates increased savings into increased investment

is certainly in the spirit of Keynesian economics, Keynes's lack of confidence

in the market was actually more fundamental and sweeping. It's not just

that the economy is bound to stumble while trying to take a step forward;

it will probably fall over backwards while just trying to stand still.

An economy operating at full employment may experience a sudden and dramatic

collapse of investment activity without there having been any change at

all in saving preferences. The predominant cause of depression, Keynes

claimed, is a sudden collapse in investment demand (p. 315). The expectations

on which investment is based are so flimsily held that virtually anything,

commonly referred to as a "change in the news," can shake business confidence.

And reduced investment means reduced employment, reduced incomes, and reduced

consumption. So, a movement off the frontier in the direction of less investment

will be compounded by a further movement in the direction of less consumption.

The result is a self-aggravating and self-reinforcing idleness of labor

and other resources.

Even

this case, in which the very nature of investment can cause the market

to be depression-prone, is not a hopeless one in the eyes of a classical

or Austrian macroeconomist. Reduced investment demand puts downward pressure

on the interest rate. A lower interest rate creates an incentive for income-earners

to save less and spend more on consumer goods. The economy is simply moved

along the production possibilities frontier in the direction of more consumption

in response to the business community's distaste for the uncertainty that

investment entails. The economy now grows more slowly, but there is no

reason that idleness should persist in markets for labor or other resources.

The Great Depression as the Michelson-Morley Experiment

In 1887, nearly three decades before Einstein published

his famous article and nearly two decades before he began to argue that

time and space are interconnected, an experiment conducted by Michelson

and Morley showed that the speed of light is independent of movements of

the source or movements of the observer. The ultimate victory of Einstein's

general theory over Newtonian theory, which deals only with a special case,

owes much to the facts about the nature of light revealed in 1887. Similarly,

the ultimate victory of Keynes's general theory over Marshallian theory,

which allegedly deals only with a special case, owes much to the fact of

the Great Depression. The key questions that put Keynesian theory to the

test seemed obvious: Is the market economy stable? Does it have self-correcting

properties? Can market forces translate changes in saving preferences or

in attitudes toward uncertainty into investment decisions that make full

use of existing resources?

The depression

had lingered on for more than half a decade at the time of the General

Theory's debut. Keynesian ideas began to revolutionize economic thinking,

and all too soon the answer to these key questions—in academia, politics,

and the media—was a confident "No." Still today, glib assertions to the

effect that the market does not work well if left to its own devices are

backed by nothing more than reminders of the fact of the Great Depression.

Academicians, politicians, and journalists have proceeded as if the

experience of the 1930s had the same significance for Keynes's theory that

the experiment of 1887 had for Einstein's. The continuing reliance on this

as-if comparison gives persistence to Keynesian myths, but a consideration

of the alternative explanations of the Great Depression reveals that the

comparison itself is a myth. In the case of Michelson-Morley, Einstein's

accounting of time, space, and mass, given an observed constancy of the

speed of light, was simple and elegant, whereas alternative accounts, which

made use of modified Newtonian theory, were complex and contrived. In the

case of the Great Depression, Keynes's accounting of employment, interest,

and money was complex and anything but elegant, whereas alternative accounts,

which made use of classical or Austrian—and subsequently Monetarist—theory,

were more consistent with the fundamentals of economics.

The Austrians,

for instance, held that the economy could accommodate changes in saving

preferences: increased saving would find its way into investment projects,

as represented by a movement along a production possibilities frontier.

They also argued that ill-conceived macroeconomic policies, nowadays called

"stimulant packages," could result in economywide unemployment. If the

central bank held the interest rate below its natural level so as to force

the economy along the frontier, the increase in investment activity would

not be sustainable. Ultimately, the consequence of forced saving is depression

rather than growth. This is only to say that, in the economic reality of

both the 1930s and the 1990s, "grow" is an intransitive verb: the economy

grows—as long as growth is consistent with consumer preferences and the

government does not stand in the way. "Grow" as a transitive verb has no

application here: the government cannot grow the economy, Bill Clinton's

campaign rhetoric notwithstanding. The Monetarists offer alternative accounts

that reinforce this general view of the relationship between government

and the economy. The "fact" of the Great Depression, then, is not confirmation

that the market economy is inherently unstable. Quite to the contrary,

it is dramatic evidence of how a market economy can be destabilized by

ill-conceived government policy. (28)

Despite

the lack of generality of the General Theory and the absence of

any actual experience that weighs obviously and heavily in its favor, there

is one sense in which Keynes's theory is Einsteinian. When Einstein himself

turned his attention away from physics and toward the economic problems

of the 1930s, he sounded like Keynes—or worse: Owing to the rapid progress

in methods of production, asserted the world's foremost physicist,

"[o]nly a fraction of the available human

labor in the world is now needed for the production of the total amount

of consumption goods necessary to life. Under a complete laissez-faire

economic system, this fact is bound to lead to unemployment. ... This leads

to a fall in sales and profits. Businesses go smash [sic], which

further increases unemployment and diminishes confidence in industrial

concerns and therewith public participation in the mediating banks; finally

the banks become insolvent through the sudden withdrawal of accounts and

the wheels of industry therewith come to a complete standstill. ... If

we could manage to prevent the purchasing power of the masses, measured

in terms of goods, from sinking below a certain minimum, stoppages in the

industrial cycle such as we are experiencing today [1934] would be rendered

impossible. The logically simplest but most daring method of achieving

this is a completely planned economy, in which consumption goods are produced

and distributed by the community."(29)

Einstein,

like Keynes, showed some concern about the dangers that loss of freedom

might entail, but the fact that he could offer such an "expression of opinion

of an independent and honest man," as he described it, gives new meaning

to Hayek's categories of science, in which physics is simple and economics

is complex.

The Problem Is...

The overarching myth kept alive by Keynesian theory

and the "fact" of the Great Depression is simply that market economies

do not have the self-correcting properties the classical economists attributed

to them and thus are inherently unstable. But we are entitled to speak

of myths because of the plurality of reasons given for the unregulated

market's instability. In the classroom, I like to play a sentence-completion

game—one that reveals just how many reasons there are, each with some basis

in the Keynesian vision. "The market economy may have its virtues, but

the problem is...." How would Keynes—or a present-day Keynesian—complete

this sentence? The problems are: (1) insufficient aggregate demand, (2)

an interest inelastic demand for investment funds, (3) an interest elastic

demand for money, (4) the "animal spirits" that rule the investment sector,

(5) the "fetish of liquidity," (6) wage and price stickiness, (7) money

illusion that keeps labor markets in disequilibrium, (8) irrational expectations

that affect asset markets, (9) transactions costs, (10) the distribution

of income, (11) the public-goods character of risk-taking, (12) the dual-decision

character of the earning-and-spending process, (13) the unknowable future,

and (14) all of the above. Being anti-Keynesian in the face of this laundry

list of problems can involve a lot of hard work. It simply won't do to

label as a myth the substantive statements suggested by each item in the

list. But dealing with all the issues associated with any one problem,

while trying to keep the other dozen problems at bay, can be analytically

demanding and rhetorically ineffective. The Keynesian vision itself, which

puts all these problems in perspective, has to be called into question.

In the

final reckoning, Keynes's vision was a double vision. The focus of his

General

Theory, with the exception of the final chapter, was the existing economic

institutions and all the problems they entailed. But Keynes's swan song

in Chapter 24, which is overlooked or summarily dismissed by almost all

interpreters (with the important exception of Allan Meltzer), envisions

an economy with a centrally directed investment sector. This economy, by

design, has none of the problems that occupied Keynes for the first 23

chapters. Nor does it have any other problems, or so the reader is led

to believe by the absence of any discussion in this direction. The Keynesian

vision, then, is a highly biased double vision. Keynesian Splenetics, which

is based on my own reading of Keynes as guided by Meltzer's "different"

interpretation, portrays the General Theory as a lopsided exercise

in comparative institutions, one in which Keynes compares capitalism-as-it-is

with socialism-as-it-has-never-been. In the context of this understanding,

the burden of proof is thrown back to the Keynesians. They must show—both

theoretically and historically—that the problems listed above are problems

which have better solutions in a socialist system than in a capitalist

system. Only by keeping debate on this level of actual comparative-institutions

analysis can those of us whose vision favors market solutions to economic

problems expect to see an eventual end to the persistent Keynesian myths.

Notes

1. John Maynard Keynes, The General

Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. New York: Harcourt, brace

and Co., 1936. (All page numbers in parentheses are references to this

book.)

2. Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard

Keynes, Hopes Betrayed: 1883-1920, New York: Viking Penguin, Inc.,

1986; and idem, John Maynard Keynes, Economist as Savior: 1920-1937,

New York: Penguin Press, 1994.

3. Robert Lekachman, Keynes' General

Theory: Reports of Three Decades, New York: Macmillan and Company,

1964.

4. Lawrence R. Klein, The Keynesian

Revolution, New York: Macmillan, 1961, p. 83.

5. Joan Robinson, "What Has Become

of the Keynesian Revolution?" in Milo Keynes, ed., Essays on John Maynard

Keynes, Cambridge: Cambridige University Press, 1975, pp. 123-31 (quotation

on p. 125).

6. Anatol Murad, What Keynes Means,

New York: Bookman Associates, 1962.

7. Alan Coddington, "Keynesian Economics:

In Search of First Principles," Journal of Economic Literature, 14:4,

pp. 1258-73 (Quotation from p. 1268).

8. Robert W. Clower, "The Keynesian

Counter-Revolution: A Theoretical Appraisal," in Clower, ed., Readings

in Monetary Theory, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1969, pp. 270-97 (Quotation

form p. 290).

9. Axel Leijonhufvud, Keynesian

Economics and the Economics of Keynes, New York: Oxford University

Press, p. 35. Yet, MIT's Paul Krugman writes that, after others had failed

at the task, "It was left to Keynes to provide a clear explanation of recessions."

Krugman, Peddling Prosperity, New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1994,

p. 26.

10. Axel Leijonhufvud, "The Wicksell

Connection," in Information and Coordination, New York: Oxford,

1981, pp. 131-202 (quotation from p. 173).

11. John R. Hicks, "Mr. Keynes and

the 'Classics': A Suggested Interpretation," Econometrica 5 (April),

1937, pp. 147-59; and Alvin H. Hansen, A Guide to Keynes, New York:

McGraw-Hill Co., Inc., 1953.

12. G. L. S. Shackle, Keynesian

Kaleidics, Edinburgh: Edinburgh Press, 1974. In his later years, Hicks

himself made a move away from his own Hydraulics and towards Shackle's

Kaleidics. In what some regard as a recantation, Hicks suggested that the

key first-order distinction in Keynes's theory is not between real and

monetary sectors but between relationships that are stable (savings out

of income and the transactions demand for money) and relationships that

are unstable (investment spending and the speculative demand for money).

Hicks, "Some Questions of Time in Economics," in Anthony M. Lang, et al.,

eds., Evaluation, Welfare and Time in Economics, Lexington, MA:

D. C. Heath and Co., 1976, pp. 135-51. Both Shackle and the latter-day

Hicks emphasize Keynes's summing-up article, "The General Theory of Employment,"

Quarterly Journal of Economics 51, 1937, pp. 209-23.

13. Roger W. Garrison, "Keynesian

Splenetics: From Social Philosophy to Macroeconomics," Critical Review

6(4), 1993, pp. 471-92.

14. Henry Hazlitt, The Failure

of the New Economics, New York: Van Nostrand Company, Inc., 1959, pp.

81-85.

15. This particular instance of origination

and attribution is documented by Don Patinkin, "On Different Interpretations

of the General Theory," Journal of Monetary Economics 26,

1990, pp. 205-43. See pp. 236-37.

16. Fred R. Glahe, Keynes's The

General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money: A Concordance, Savage,

MD: Roman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1991. Parts of my discussion

here are drawn from my review of Glahe's book, Roger W. Garrison, "Reflections

on a Keynesian Concordance," Austrian Economics Newsletter 12:1

(Spring) 1992, pp. 10-12.

17. Don Patinkin, "Meltzer on Keynes"

Journal

of Monetary Economics 32, 1993, pp. 347-56.

18. Patinkin, "On Different Interpretations,"

p. 227.

19. Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes,conomist

as Savior: 1920-1937, p. 487.

20. Quoted from a 1936 review. Skidelsky,

John Maynard Keynes, Economist as Savior: 1920-1937, p. 585.

21. Also, Galbraith points out the

that the early working title of Keynes's book was simply The General

Theory of Employment [which became the title of his 1937 summing-up

article]. James K. Galbraith, "Keynes, Einstein, and Scientific Revolution,"

The

American Prospect 16 (Winter), 1994. pp. 62-67. If the idea of Keynes

borrowing a vision from Einstein seems strange, consider Stephen Hawking's

use of a Keynesian theme in his account of creation: "where did the energy

come from to create this matter [of the early universe]? The answer is

that it was borrowed from the gravitational energy of the universe. The

universe has an enormous debt of negative gravitational energy, which exactly

balances the positive energy of the matter. During the inflationary period

the universe borrowed heavily from its gravitational energy to finance

the creation of more matter. The result was a triumph for Keynesian economics:

a vigorous and expanding universe, filled with material objects. The debt

of the gravitational field will not have to be paid until the end of the

universe." Stephen Hawking, Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other

Essays, New York: Bantam Books, 1993. p. 97.

22. At issue here is J. S. Mill's

fourth fundamental proposition concerning capital: "Demand for comodities

is not demand for labor," or, to put it in Keynesian terms, the demand

for N does not move in lockstep with the demand for Z. The

centrality of capital in macroeconomic theorizing is the theme of Roger

W. Garrison, "Austrian Capital Theory and the Future of Macroeconomics."

in Richard M. Ebeling, ed., Austrian Economics: Perspectives on the

Past and Prospects for the Future, Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College

Press, 1991, pp. 303-24.

23. Friedrich A. Hayek, The Pure

Theory of Capital, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1941, p. 374,

n.1.

24. Friedrich A. Hayek, Prices

and Production, New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1967; and Hayek, Monetary

Theory and the Trade Cycle, New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1966.

25. Allan Meltzer, Keynes' Monetary

Theory: A Different Interpretation, Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1988, p. 311.

26. For an attempt to remedy this

lack of integration, see Roger W. Garrison, "Linking the Keynesian Cross

and the Production Possibilities Frontier," unpublished manuscript, 1994.

27. Hayek, Prices and Production,

pp. 49-54.

28. Hayek, Prices and Production,

pp. 54-60.

29. Albert Einstein, "Thoughts on

the World Economic Crisis," in Einstein, Ideas and Opinions, New

York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1982, pp. 87-91.

|

The Keynesian

legacy is twofold. In the academic arena, Keynesian theory has caused professional

economists who are generally sympathetic to the ideal of a free society

to doubt that an unbridled market economy can bring us prosperity and stability.

In the political arena, Keynesian ideas have served as a justification

for bridling the market economy with fiscal and monetary policies. The

Full-Employment Act of 1946 and much subsequent legislation have allowed

policymakers to use the powers of taxing, spending, and money creation

in their attempts to achieve the prosperity and stability that is supposedly

out of the market's unassisted reach. Keynesian myths persist today largely

because of the uncritical presumption that the economy's sluggishness and

instability are to be attributed to fundamental defects in the market system

rather than to the perversities of the very policies intended to compensate

for those supposed defects.

The Keynesian

legacy is twofold. In the academic arena, Keynesian theory has caused professional

economists who are generally sympathetic to the ideal of a free society

to doubt that an unbridled market economy can bring us prosperity and stability.

In the political arena, Keynesian ideas have served as a justification

for bridling the market economy with fiscal and monetary policies. The

Full-Employment Act of 1946 and much subsequent legislation have allowed

policymakers to use the powers of taxing, spending, and money creation

in their attempts to achieve the prosperity and stability that is supposedly

out of the market's unassisted reach. Keynesian myths persist today largely

because of the uncritical presumption that the economy's sluggishness and

instability are to be attributed to fundamental defects in the market system

rather than to the perversities of the very policies intended to compensate

for those supposed defects.

add

to the stock of capital, increasing the economy's capacity for producing

both categories of goods in the future.

add

to the stock of capital, increasing the economy's capacity for producing

both categories of goods in the future.