vol. 20, no. 2 (Summer), 1988, pp. 207-234

Phillips Curves And Hayekian Triangles:

Two Perspectives on Monetary Dynamics

Don Bellante and Roger W. Garrison

I. Introduction I. Introduction

During different phases of the Keynesian episode, the monetary theories

offered first by Keynes and later by the Keynesians have been judged by

changing standards. The standards changed along with the changing perceptions

of what constituted the most viable alternative to the Keynesian vision.

"[T]here was a time," wrote John Hicks (1967, p. 203), "when the new theories

of Hayek were the principal rival of the new theories of Keynes." But times

changed, and Milton Friedman (1969d), with his restatement of the quantity

theory of money, became the dominant alternative to Maynard Keynes. And

eventually, Friedman's Monetarism gave way to New Classicism and the idea

of "Rational Expectations."

The profession has been

treated to exhaustive comparisons of Keynes and then Keynesians with the

various opposing schools, but comparisons of the sequential alternatives

to Keynesianism have been all but lacking. The present paper begins to

fill this void by offering a critical comparison of the Monetarists and

the Austrians as represented by Friedman and Hayek.(1)

A statement by Robert Lucas (1981, p. 4) suggests how such a comparison

can be undertaken: "...I see no way to account for observed employment

patterns that does not rest on an understanding of the intertemporal substitutability

of labor." Lucas's concise way of identifying the understanding that explicitly

underlies his theories (and implicitly underlies Friedman's) hints at an

alternative way of accounting for observed unemployment patterns. While

Monetarism and New Classicism are based on the intertemporal substitutability

within the market for labor, Austrianism is based on the intertemporal

complementarity within the market for capital goods.

Differences between the

monetary theories of Friedman and those of Hayek, then, can be spelled

out in terms of the markets (for labor and for capital, respectively) that

serve as a focus for each.(2) With attention

to the major themes of each theorist, Sections II and III identify the

relevant aspects of monetary disturbances as seen by Friedman and as seen

by Hayek. Focusing on both substance and method, Section IV offers a critical

comparison of the two perspectives. Section V points out some implications

in terms of the conventionally defined categories of unemployment, monetary

lags, and the concept of "full" employment; and Section VI provides a summary

view.

II. Friedman (and the Monetarists) on Monetary Dynamics

With conventional qualifications and allowances for real growth, increases

in the supply of money lead, in the long run, to proportionate increases

in the general price level. This proposition, which constitutes the kernel

of truth in the quantity theory of money, is not in dispute. But the nature

and significance of the monetary dynamics, the market process that translates

the initial cause into its ultimate effect, is and has long been a matter

of much controversy. This issue, in fact, is what separates the Monetarists

from the Austrians and gives scope for interpretation within both schools.

Friedman appears to be of

two minds on the issue of monetary dynamics—the transmission mechanism

linking money to prices. On occasions where the focus is on long-run comparative-statics

results, it is simply admitted that he (along with Anna Schwartz) has "little

confidence in [their] knowledge of the transmission mechanism, except in

such broad and vague terms as to constitute little more than an impressionistic

representation rather than an engineering blueprint" (Friedman, 1969b,

p. 222). But on occasions where the focus is on the transmission mechanism

itself, such as the market process that traces out a short-run Phillips

curve, there is an accounting of the the mechanism in terms of the market

for labor that would rival any blueprint(3)

(Friedman, 1976). These monetary dynamics, which are used by Friedman to

explain the short-run nature of the negatively sloped Phillips curve and

to suggest the existence of a vertical long-run Phillips curve, can be

used as a basis for evaluating the Monetarist view and for comparing it

to the alternative offered by the Austrians.

The monetary dynamics envisioned

by Friedman hinge on the sequential effects of perceived relative-price

changes in the market for labor. A number of heuristic assumptions about

the market for capital goods and about income effects in commodity markets

are invoked. These assumptions are required to narrow the focus so that

the Monetarists' story can be told. The lack of discussion in this context

of the allocation of capital goods or of the short-run effects of a monetary

injection within the market for capital goods is evidence enough that such

considerations are no part of the story.(4)

Implicitly, one of several alternative constructions is adopted: (1) Real

capital is taken to be completely homogeneous, or—to use the fiction invented

by Frank Knight—it is treated as a "Crusonia plant." (2) The structure

of real capital, which admittedly consists of heterogeneous elements, is

fixed. It cannot or, for some reason, is not altered—even in the short

run—as a result of a monetary injection. (3) Allocations within the market

for capital goods are (somehow) always governed, whether in the presence

or the absence of monetary disturbances, by "real factors only." This third

construct is in the spirit of the New Classicism.

One of these three or some

effectively similar construction or assumption must underlie any macroeconomic

theory that ignores the allocation of resources within the capital-goods

sector. Implicit assumptions of this sort about capital goods are not at

all at odds with the Chicago tradition more broadly conceived. The inattention

to capital theory stems from Frank Knight's grappling with the thorny issues

and conceptual difficulties that inhere in this subject matter (Knight,

1934). In general, Monetarists have taken comfort in the Knightian view

that the structure of capital, particularly the intertemporal structure,

can be safely ignored, and that theories in the Austrian tradition, which

make use of such concepts as "roundaboutness" and "stages of production,"

are especially misguided.(5)

The Knightian view of capital

permits the Monetarists to focus exclusively on the market for labor. But

at least two additional assumptions are needed to limit the focus to the

relative-price effects in the labor market. Distribution effects (who gets

the new money) and differential income effects (how it gets spent) must

be removed from consideration. Friedman's heuristic device for short-circuiting

the distribution effects is to assume that increases in the money supply

are brought about by a one-time dropping of money from a helicopter in

such a way that each individual picks up the new money in direct proportion

to the amount already in his possession.(6)

The differential income effects of "helicopter money"—as it has come to

be called—are assumed away. This mode of theorizing reflects the implicit

assumption that differential income effects are in fact negligible or the

heuristic assumption that indifference curves are both identical across

agents and homothetic.(7)

Within this theoretical

construction, the Quantity Theory holds in its strongest form, and any

divergence in the pattern of prices between the initial injection of money

and the eventual increase in the price level is purely stochastic. Thus,

disequilibrium relative-price movements within the markets for both capital

goods and final products are taken to be unsystematic. No generalizations

about such movements can be made. But movements in the price of labor relative

to the price of final output are systematic in the Monetarist view.

And the temporal pattern of these movements depend in a critical way on

differences in the ability of workers and of employers to perceive the

price changes most relevant to each.(8)

The spending of newly created helicopter money begins to bid up the prices

of final products in unsystematic ways. The individual worker, who clearly

perceives his yet-unchanged nominal wage, has no clear perception of the

change in his real wage—depending, as it does, on the change in some index

of final-product prices. The employer, whose perception of the general

price level is no better than the workers', is motivated by a different

concern. From the employer's perspective, the relevant real wage is the

Ricardian real wage, which depends upon a single price—the price of the

product that the employer produces. If the output price has increased,

the wage that he pays to the workers—relative to the output price—has clearly

decreased. Alternatively stated, workers and employers alike have no clear

perception of the real wage, where real is understood in the market-basket,

or Fisherian, sense; but employers have a clear perception of the real

wage, where real is understood in the Ricardian sense.)

The spending of newly created helicopter money begins to bid up the prices

of final products in unsystematic ways. The individual worker, who clearly

perceives his yet-unchanged nominal wage, has no clear perception of the

change in his real wage—depending, as it does, on the change in some index

of final-product prices. The employer, whose perception of the general

price level is no better than the workers', is motivated by a different

concern. From the employer's perspective, the relevant real wage is the

Ricardian real wage, which depends upon a single price—the price of the

product that the employer produces. If the output price has increased,

the wage that he pays to the workers—relative to the output price—has clearly

decreased. Alternatively stated, workers and employers alike have no clear

perception of the real wage, where real is understood in the market-basket,

or Fisherian, sense; but employers have a clear perception of the real

wage, where real is understood in the Ricardian sense.)

Quantity adjustments in

the labor market are made in ways that correspond to the differing perceptions

in real-wage movements. The behavior of workers, who make their labor-leisure

decisions on the basis of yet unchanged perceptions, is depicted by an

unchanged labor supply curve; the behavior of employers who now enjoy higher

output prices is depicted by a rightward shift in the demand for labor.(9)

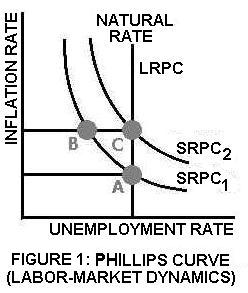

The nominal wage rate rises as does the level of employment. (Figure 1

shows the corresponding movement (from A to B) along the initial Short-run

Phillips Curve.) The higher nominal wages paid to a larger number of workers

exert upward pressure on the prices of final products; increases in output

exert downward pressure on final-product prices. And with the passage of

time, workers begin to get a clearer perception of their real wage rate.

A temporal pattern of the real wage rate is traced out by a series of iterative

steps in which the reinforcing and counteracting forces interact. In the

end, after a "long and variable"—and fundamentally indeterminate—time lag,

the worker-employer perception differential is eliminated; the short-run

Phillips curve shifts rightward. The level of employment, the level of

output, and the real wage (both Fisherian and Ricardian) return to the

levels that characterized the economy before the monetary injection. (Point

C in Figure 1 differs from point A only in terms of absolute prices and

wages.)

III. Hayek (and the Austrians) on Monetary Dynamics

If Frank Knight accounts for the Monetarists' inattention to capital

theory, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1959) accounts for the Austrians' preoccupation

with it. Where Friedman's treatment of monetary dynamics requires some

key assumptions about the workings of the market for capital goods, Hayek's

treatment(10) requires similar assumptions

about the workings of the labor market. Recognizing this symmetry allows

us to describe the alternative treatments in a way that facilitates a comparison.

More often than not, Hayek's

assumptions about labor, like Friedman's assumptions about capital, are

implicit. Labor skills are assumed to be non-specific. Individual occupations

are defined in terms of the particular capital goods that are complementary

to labor. Wage rates are flexible, but not perfectly flexible. Workers

can be bid away from some occupations and into others, but not instantaneously.

Adjustments in the labor market that involve a reduction in labor demand

in some occupations will be characterized by temporary increases in the

level of unemployment—the greater the adjustment, the greater and longer-lasting

the temporary increase. With allowance for frictions of this sort, workers

are able correctly to perceive and respond to changes in the pattern of

real wage rates. Expectations about wage rates and prices can come into

play—but not expectations whose formulation requires a theoretical understanding

of economic relationships, such as (correct or "rational") expectations

about the upper turning point of a business cycle.

It might be noted at this

point that Lucas (1981, pp. 215-17) sees a certain kinship between his

own ideas and those of Hayek. But Lucas parts company with the Austrians

when he treats knowledge of the economy's structure in the same

way as knowledge within the structure. Hayek (1948b, pp. 79-81)

makes a first-order distinction between theoretical knowledge and knowledge

of the marketplace. Market participants can be expected to make use of

information conveyed by prices along with other particular knowledge that

they might have, but they cannot be expected to know—even in a probabalistic

sense—the parameters of the economy's structure. That is, they cannot be

expected to know, or to behave as if they know, the answers to questions

that economists have been debating amongst themselves for more than two

hundred years.(11)

The assumptions spelled

out above about the workings of the market for labor allow the Austrians

to deal with monetary dynamics exclusively in terms of the market for capital

goods. The dynamics within the capital-goods market, coupled with these

assumptions, will have clear implications about the corresponding pattern

and time path of the employment of labor. The effects of a monetary disturbance

within the market for capital goods reflect several considerations. Capital

goods in the Austrian view are heterogeneous in the extreme, and the structure

of capital involves multidimensional complexity. Individual capital goods

are characterized by different degrees of specificity and are related to

one another, both intertemporally and atemporally, with various degrees

of substitutability and complementarity.(12)

Thus, a set of heuristic assumptions about the capital structure is required

to allow the identification of its most essential features and to render

the treatment of monetary dynamics tractable.

In the Austrian view, the

central problem in macroeconomics is the problem of intertemporal discoordination.

(O'Driscoll, 1977, pp. 70-79; Garrison, 1984, 1985) Whether the focus is

on the coordination of investment decisions with consumption decisions

or on the time-pattern of macroeconomic magnitudes over the course of a

business cycle, the temporal element is essential to the macroeconomic

perspective. Hayek incorporated this temporal element into his monetary

dynamics by focusing on the intertemporal aspects of the economy's capital

structure. To avoid undue complexity, Hayek envisioned a heavily stylized

production process.

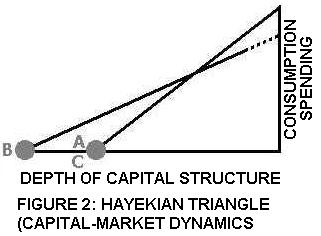

His vision gives recognition,

sometimes explicitly and sometimes implicitly, to a set of corresponding

heuristic assumptions. Each production process is characterized by a modifiable

sequence of inputs and a point output; some production processes are more

time-consuming than others. The sequence of inputs is conceived as consisting

of "stages" of production. The once-

famous Hayekian

triangles(13) represent a stylization of

the entire economy's production process (See Figure 2): The horizontal

leg represents the time element in the process—the depth of the capital

structure. In the simplest case this leg represents the time that sepatates

the earliest stage of production from the final output; the vertical leg

represents the nominal value of the final output. The height of the hypotenuse

at successive points in time represents the value of semi-finished goods

as they move through time from the earliest to the latest stage of production.(14) famous Hayekian

triangles(13) represent a stylization of

the entire economy's production process (See Figure 2): The horizontal

leg represents the time element in the process—the depth of the capital

structure. In the simplest case this leg represents the time that sepatates

the earliest stage of production from the final output; the vertical leg

represents the nominal value of the final output. The height of the hypotenuse

at successive points in time represents the value of semi-finished goods

as they move through time from the earliest to the latest stage of production.(14)

Capital goods can be shifted—within

limits—from one production process to another in response to relative-price

changes. More importantly, capital goods can be shifted from one stage

of production to another in ways that modify the intertemporal pattern

of output. Some types of capital goods that are employed in the earlier

stages of production (or that, with some modification, can be so employed)

may be needed in the later stages of production as well. That is, while

competing for the use of individual capital goods, the stages themselves

exhibit a certain degree of intertemporal complementarity. There is no

one-to-one relationship between stages of production and business firms.

Some firms may operate within one stage, some in several sequential stages,

and some in different stages of different production processes.

Spelling out the characteristics

of the Hayekian structure of production is, by itself, almost enough to

specify the nature of the corresponding monetary dynamics. The general

pattern of events set into motion by a monetary injection can be identified

as soon as the method of injecting the new money is specified. Because

of the historical relevance, Hayek assumed that the new money is injected

through credit markets—that the central bank, in effect, pads the supply

of loanable funds with newly created money.(15)

Clearing the market for

loanable funds in the face of such a monetary injection requires that the

rate of interest fall until the quantity of funds demanded matches the

increased supply.(16) In turn, this lowered

rate of interest has implications for the intertemporal structure of capital.

To the extent that the temporal relationship between the various types

of capital goods and the ultimate output of the production processes is

perceived by entrepreneurs, the prices of the capital goods will be affected

in a systematic way. In the earlier phases of the market's reaction to

the credit expansion, the greater the time between the use of the capital

good and the emergence of the ultimate output, the greater the relative

increase in the price of the capital good. This pattern of relative-price

changes follows from the application of standard discounting techniques.

There will be a corresponding pattern of quantity adjustments. Capital

will be bid away from relatively less time-consuming production process

into relatively more time-consuming processes and away from relatively

late stages of production into relatively early stages of production. Marginal

adjustments of these sorts will be made throughout the capital structure

as firms seek to take advantage of the favorable credit conditions. In

Figure 2 the shift towards more time-consuming processes is represented

by a movement from A to B. (The change in the slope of the hypotenuse reflects

smaller profit differentials between the stages of production, which in

turn reflect cheaper credit.)

The later phases of this

dynamic process are marked by a reversal of the price and quantity movements

that characterized the earlier phases (Hayek, 1967, p. 58). The passage

of time takes production projects that were begun as a result of credit

expansion into their later stages. Some of these later stages require the

use of capital that was used up in—or irrevocably committed to—earlier

stages. That is, the money-induced expansion caused more capital to be

committed to the earlier stages of production without providing the additional

resources—as would have been provided had the expansion been savings-induced—necessary

for the completion of all the production processes. In Figure 2 the value

of the production projects in their final stages is represented by a broken

line, indicating that a credit-induced boom cannot be sustained.

Capital goods complementary

to the yet-uncompleted production processes are now in short supply. Their

prices are bid up, and as a result of these higher prices, the demand for

credit increases. The rate of interest, which had been artificially low

during the monetary expansion, is now bid up. Two significant differences

between the Austrian and the Monetarist views can be noted here: First,

because of intertemporal complementarity, the initial investment raises

the demand for capital(17); second the

resulting rise in the interest rate is separate from any Fisher effect,

which depends upon a rising price level.(18)

Both directly through the

market for capital goods and indirectly through credit markets, the prices

of capital goods committed to the early stages of production are bid down.

Uncommitted capital goods are bid away from the earlier stages of production

and into the later stages.(19) But in this

phase of the dynamic process, marginal adjustments may not be possible.

Some capital goods attracted to the earlier stages of production by the

monetary expansion may not be retrievable. As a consequence, many production

projects may have to be abandoned; many others can be completed but only

with a great delay and/or at a much higher cost than could have been anticipated.

(The claim, made in the spirit of the New Classicism, that market participants

will

anticipate the money-induced capital shortage rings hollow. Such an anticipation

would require that they know—or behave as if they know—the "real scarcities"

independent of the price system which supposedly communicates that information

to them. In the Austrian view, if a monetary injection distorts the price

signals, market participants will be economizing on the basis of erroneous

information.)

This later phase of the

adjustment process takes on the characteristics of a crisis, a sharp down-turn.

But with time, some types of capital can be liquidated to accommodate the

excess demands for other types. Eventually, the economy's capital can be

restructured in a way that reflects real resource availabilities, and the

credit market can be adjusted to reflect the supply and demand for loanable

funds. Abstracting from the capital that is lost forever as a result of

the credit expansion and from possible long-run effects on the distribution

of income, the rate of interest and the corresponding structure of production

will return to the level and configuration that characterized the economy

before the credit expansion.

Figures 1 and 2 can serve

to depict the correspondence between the Monetarist and the Austrian views.

Arguing respectively in terms of the wage-rate effect on the employment

of labor and the interest-rate effect on capital utilization, Friedman

and Hayek have traced out the consequences of a monetary injection from

A to B to C, where, in both diagrams, points A and C represent identical

sets of real parameters. Point B represents—in Figure 1—a rate of unemployment

temporarily and unsustainably below the (Friedmanian) natural rate and—in

Figure 2—a depth of capital temporarily and unsustainably maintained by

a loan rate of interest kept below the (Wicksellian) natural rate.

To this point the Austrian

story has been told exclusively in terms of the market for capital goods.

Yet a major purpose of the story is to account for the cyclical unemployment

of labor. But filling in the blanks about how the labor market is affected

by the dynamics in the capital market is not difficult. In the trivial

case of perfect wage flexibility and instantaneous adjustments, there need

be no unemployment at all. Labor would simply be shifted around during

the unfolding of the dynamic process so as to be employed in ways consistent

with the changing pattern of relative prices.(20)

This is clearly not what Hayek had in mind.

The recognition that labor

is complementary to (some) capital and that frictions inherent in the market

process prevent adjustments from taking place instantaneously is all that

is required to translate the story about capital into a story about labor.

During the early phases of the dynamic process, there is a net increase

in the demand for labor. The new money injected through credit markets

is used not only to bid workers away from some jobs and into others but

to attract new workers as well. To use Friedman's terminology, unemployment

falls below its natural rate.

But during the late phases

of the process, there are actual decreases in the demand for labor in the

early stages of production. And the increases in the demand for labor in

the later stages is only partially offsetting—due to the shortage of complementary

capital goods. The frictions involved in the economy-wide movements of

labor out of the early stages and into the late stages coupled with the

net reduction in the demand for labor account for a considerable amount

of supernatural unemployment during this phase of the dynamic process.

Once the misallocated capital

has been liquidated and the wage rates have adjusted to the underlying

market conditions, the cyclically unemployed workers can be reabsorbed.

In Hayek's story as in Friedman's, unemployment eventually returns to its

natural rate.

IV. A Critical Comparison

While the two views of monetary dynamics spelled out in the previous

two sections differ in important respects, they are in several fundamental

respects quite similar. Comparing the differences, then, must be prefaced

by a clear recognition of the underlying similarities. Five points of commonality

are noteworthy: (1) Both theories can be fully squared with the kernel

of truth in the quantity theory of money. (2) Both theories deal with disequilibrium

phenomena, but neither denies that equilibrating forces dominate in the

end. (3) Both hinge in a critical way on the distinction between short-run

effects and long-run effects. (4) Both involve a market process that is

necessarily, or endogenously, self-reversing. Monetary disturbances cause

certain kinds of distortions in market signals. These distortions give

rise in the short run to movements in certain prices and quantities, movements

which in the long run create market conditions for counter-movements in

those same prices and quantities. (5) With appropriate qualifications (about

what constitutes the long-run) both theories are characterized by monetary

disturbances whose short-run effects are non-neutral but whose long-run

effects are neutral.

With allowance for these

points of commonality, Friedman and Hayek are offering in some respects

complementary views, in other respects competing views. Our comparison

will attempt to separate the two kinds of differences. Comparing aspects

of the two views that are at odds with one another must await a closer

look at each view separately. But ways in which the two views are different

but complementary can be readily identified.

At the root of these kinds

of differences is the fact that Friedman focuses his analysis on the market

for labor while Hayek focuses his on the market for capital goods.(21)

The trade-off that gets distorted by monetary disturbances is labor vs.

leisure for Friedman and goods now vs. goods later for Hayek. And due in

large part to the differing natures of labor and capital (the more radical

heterogeneity of capital as compared to labor(22)),

Friedman argues in terms of substitutability and Hayek in terms of complementarity.(23)

In an important sense there

is simply no scope for conflict here. Labor-leisure preferences and intertemporal

preferences interact with the perceived constraints that are relevant to

each. The dimensions of the two market processes can be seen as orthogonal

to one another. Trading off labor against leisure in a sequence of periods

can be understood as substituting labor in some periods for labor in others.

Thus, with both views laid out intertemporally, we see that Friedman is

dealing with the intertemporal substitutability of labor while Hayek is

dealing with the intertemporal complementarity of capital. Spelled out

in these general terms, then, we have a harmony, rather than a conflict,

of views.(24)

1. A Critical Retelling of Friedman's Story

But when we turn again to the specifics of the market processes envisioned

by Friedman and Hayek, we see first-order differences. Some of these differences

put the two views at odds with one another—or at least allow for a preference

of one over the other on the basis of plausibility or fruitfulness. Identifying

these differences and their significance can begin with a critical assessment

of Friedman's view, which we preface with a recognition of existing criticism

in the literature.

Sketchy expositions of the

Monetarist view have given much scope for misinterpretation. Gardner Ackley

(1983, p. 10), for instance, sees the Monetarist dynamics purely in terms

of "tricks" played on employers and workers. It is a "trick for an inflation

to fool both employers and workers—in opposite directions—about

the movements of the real wage paid by one and received by the other."

But to call this a trick is to miss Friedman's point. The "real wage" means

one thing to workers and something else to employers. Neither workers nor

employers have a clear perception about what is happening to the general

price level, but both are responding in conventional ways to the incentives

that they face. Recognizing these incentives gives Friedman's view a microeconomic

footing and insulates it against criticism of the type offered by Ackley.

Another criticism of Friedman's

view (Birch, Rabin, and Yeager, 1982) is based on a perceived contradiction

between the market process envisioned and the equation of exchange.(25)

The familiar identity MV = PQ implies that when M, or more properly MV,

increases, the corresponding increase in PQ is split in some way

between an increase in P and an increase in Q. That is, Q can increase

only to the extent that P does not increase. By contrast and according

to the Monetarist account of the dynamic process, it is increases in P

that cause increases in employment and hence increases in Q. That is, Q

increases to the extent that P does increase—hence the perceived contradiction.

But what appears at first blush to be a contradiction is in fact a manifestation

of a self-reversing process. There is nothing logically contradictory

about a process in which P begins rising before Q but in which Q falls

as P becomes fully adjusted to the increase in M. While the Ps and the

Qs can be squared with the equation of exchange at each point in the process,

Q's initial upturn and inevitable downturn, which reflect similar movements

in the employment of labor, constitute the essential self reversal that

lies at the heart of the Monetarist view.

Our own criticism is fundamentally

different from the ones identified above. While the sequence of movements

in P and Q are not evidence of a contradiction, they are evidence of a

certain anomaly in the Phillips Curve story. An initial rise in prices

is a prerequisite to any movement along a short-run Phillips curve, but

the story accounts inadequately for the nature of this initial rise. To

make the story stick we must recognize that there is some other, logically

prior, market process that is set into motion by a monetary injection.

The process can be easily identified by drawing more broadly from the Monetarist

literature. Helicopter money adds to each individual's cash balances, thereby

inducing greater spending and the bidding up of prices (Friedman, 1969c,

p. 5). But if buyers of labor services receive their pro-rata share

of the helicopter money, they would be bidding up the price of labor at

the same time. The simultaneous rise in the price of output and the price

of labor would preclude the fall (as perceived by the employer) in the

real wage, which itself constitutes a critical aspect of the self reversing

dynamic process. The real-cash-balance effect, then, becomes the whole

story rather than a prelude to the Phillips-curve story.

The Phillips Curve story

can be saved by assuming a monetary injection in which the new money falls

first into the hands of consumers and only later into the hands of producers.

While this kind of assumption, which highlights a particular distribution

effect, violates the spirit of Monetarism, it allows in a straightforward

way for a variation on the Austrian theme. We turn now to consider the

Austrian alternative.

2. Heuristic Assumptions and Domain Assumptions

The assumptions made by Friedman and Hayek about the nature of the

hypothesized monetary injection are not just two alternative assumptions

that serve the same purpose. Friedman's assumption (that money is dropped

from a helicopter) is a heuristic assumption. It is a deliberate

fiction whose purpose is to bypass any questions that relate directly to

the actual injection of money while still allowing for the derivation of

implications that can be tested empirically. (Friedman's uninhibited use

of such fictions identifies his method as instrumentalism.(26))

Hayek's assumption that

money is injected through credit markets is a domain assumption.(27)

In many instances money actually is injected through credit markets.

Thus Hayek's story applies directly and without modification to those instances.

A lower rate of interest resulting from the credit expansion increases

the quantity of credit demanded. Given the relative volumes of commercial

lending and consumer lending, we can say that the new money falls first

into the hands of producers and only later into the hands of consumers.

This disproportionate distribution of the new money is consistent with

Hayek's story about the effect of a monetary injection on the structure

of capital: Production for future consumption is temporarily favored

over production for present consumption.

For instances in which money

is injected by some other means, Hayek's story applies only after suitable

modifications are made. Suppose, for example, that a monetary expansion

takes the form of increased transfer payments to consumers. This type of

monetary injection would temporarily favor present consumption over

future

consumption. Capital goods would be reallocated accordingly. In many respects,

the self-reversing market process triggered by such an injection would

be a mirror image of the process triggered by a credit expansion. Capital

goods in the later stages of production would be first in short supply

and subsequently in surplus. The demand for labor would rise and then fall

as workers were bid into the later stages of production only to become

unemployed when the demand for present consumption fell to its "natural"

level. The downturn associated with such a transfer expansion may

be less severe than one associated with a credit expansion if only

because short-term capital can be liquidated more quickly than long-term

capital.

Two observations are warranted

here. First, Friedman needs to incorporate a transfer expansion, or something

like it, into his theoretical construction if his Phillips curve story

is to become coherent. Second, inflation-rate and unemployment data that

suggest a negatively sloped short-run Phillips curve and a vertical long-run

Phillips curve are consistent with Hayek's story whether the new money

is lent into existence or transferred into existence.(28)

Before we suggest what empirical, or historical, considerations might constitute

a basis for choosing between the alternative stories offered by Friedman

and Hayek, we turn to one further issue—the issue of generalizability.

3. Generalizability

Any theoretical construction that suggests how a particular market

works may be more or less generalizable—adaptable to different circumstances

or extendable to other markets—depending in large part upon the nature

of the assumptions used in the construction. The discussion above suggests

that theories based on domain assumptions are more generalizable than theories

based on heuristic assumptions. Hayek's story can be adapted to apply to

circumstances in which the new money favors consumption activity over investment

activity even though it was first told the other way around. The story

can be generalized to recognize that monetary expansion can cause intertemporal

discoordination—in one direction or the other—depending upon the particular

device used to inject the new money. In recent years Hayek has generalized

his own story even further by recognizing that monetary expansion causes

a self-reversing discoordination in many markets, whether or not it causes

any intertemporal discoordination (1975a, pp. 23-24). By generalizing in

this way, Hayek has not at all changed his mind about the effects of monetary

expansion, he has simply recognized that the domain (credit expansion)

that once dominated his subject matter is no longer so dominant. But money-induced

discoordination—of one sort or another—still dominates the story.(29)

Friedman's story makes use

of a monetary helicopter whose precise function is to assume away the discoordination

that Hayek's story deals with. The monetary helicopter does not constitute

one domain from which the theory can be extended; it constitutes the intentional

neglect of all such domains. The Friedmanian helicopter, like the Walrasian

auctioneer in a different story, should be seen as a "red flag," a marker

where something important has been left out of account so that some other

part of the story could be told. From this perspective we can admire the

outrageousness of the particular fiction employed: the helicopter is a

red flag that virtually no one could fail to see. But a red flag is no

basis for generalization. If we go back and take into account the effects

of actual monetary injections, we do not get a generalization of Friedman's

story; we get Hayek's story.

Hayek's story is generalizable

in another important respect. The task of identifying the effects of credit

expansion was made tractable by employing a heuristic assumption about

the structure of capital-using production processes—the assumption of multi-period

inputs and a point output. This particular assumption allowed for the abstraction

from many complexities while it retained the essential element—the time

element—in the analysis. Once the story is told in its most tractable form,

then, it can be generalized and extended to take into account some of the

complexities that were initially assumed away.(30)

Production processes with multi-period outputs can be taken into account

as well as processes that make use of capital goods of a greater or lesser

degree of durability or whose final output is a durable consumer good.

And by recognizing the ways in which the market for "human capital" is

like the market for capital goods, Hayek's analysis can be extended in

a direct way to labor markets as well (Bellante, 1983).

Unfortunately, Hayek's attempt

to tell his story in the contexts of several different circumstances was

seen as evidence of confusion on Hayek's part. In response to criticism

that he assumed an initial state of full employment and placed too much

emphasis on changes in the terms of credit, Hayek (1975c, pp. 3-37) offered

an alternative account in which widespread unemployment was assumed and

the loan rate of interest was held constant. The resulting story was then

criticized (Kaldor, 1942) on the grounds that it contradicted Hayek's own

earlier rendition. By uncritically adopting Kaldor's assessment of what

he dubbed the "concertina effect," modern critics have failed to appreciate

the adaptability, the generalizability, that characterizes Hayek's formulation.(31)

A similar sort of generalization

and extension is not possible for Friedman's story. The essential feature

on which his story depends is unique to the particular context in which

it is told. For Friedman, the differing perceptions of workers and employers

is what gives rise to the story; they are what "drive the system." The

market process that Friedman identifies has no direct counterpart in the

market for capital goods. The owner of a diverse capital stock, for instance,

is unlikely to have perceptions that differ in a systematic way from those

who may buy the services of that capital stock. Such perception differences

are even less likely in the more prominent cases in which capital goods

are owned indirectly through financial markets. Thus, independent of any

empirical considerations, we have some basis for preferring Hayek's story

over Friedman's. Hayek's domain assumptions and even his heuristic assumptions

allow for generalization and extension in ways that Friedman's do not.

Hence, Hayek's theoretical construction is the richer, the more fruitful,

of the two.

4. Historical Applications and Policy Implications

Extensive empirical testing has favored Friedman's view of the nature

of the short-run Phillips curve over beliefs or hopes that there is a more

permanent trade-off between inflation and unemployment. But this same empirical

testing provides no clue at all about the nature of the market process

that moves the economy along a short-run Phillips curve and then shifts

that curve so as to conform with the long-run vertical Phillips curve.

That is, the testing allows to us choose between a Keynesian view and a

Friedman-Hayek view, but not between the Friedman view and the Hayek view.

Direct empirical evidence

about the nature of the monetary dynamics involved in adjusting the economy

to a monetary injection may be all but impossible. Directly substantiating

Friedman's story would require data on perceived real wage rates; directly

substantiating Hayek's story would require the quantification of actual

changes in the complex structure of capital.(32)

We must look for implications of the two views that allow for empirical

differentiation. As it turns out, our comparison of the two views provides

the needed clue about differing implications.

In Friedman's story a general

rise in prices of final output is a necessary link in the self-reversing

market process triggered by monetary expansion. Without this price inflation,

which has a different significance for workers and for employers, there

is no story to tell. While Hayek's story allows for price inflation, his

story does not depend upon it (1967, pp. 22-30; 1975b, pp. 104, 121, 196,

and passim). An initially depressed interest rate followed by subsequent

resource constraints within the market for capital goods can serve alone

as the basis for the self-reversing market process envisioned by Hayek.(33)

This realization that price inflation plays a leading role in one story

and, at best, a supporting role in the other allows us to identify important

differences in the way the two stories are used not only in the interpretation

of history but also in the prescription of policy.

Historical episodes in which

monetary expansion is accompanied by an unchanging price level are interpreted

differently by Friedman and Hayek. The decade of the 1920s provides the

most dramatic illustration of this difference. Real economic growth during

this decade, which in the absence of monetary expansion would have produced

a decline in the price level, served instead to offset the inflationary

effects of the monetary expansion. The self-reversing process that, in

Friedman's view, characterizes other episodes of monetary expansion does

not get triggered in this one. There is no Phillips-curve story to tell.

Economic problems that surfaced at the end of the '20s are not, according

to the Monetarist view, a result of a market process that began much earlier

in the decade. The economic downturn is blamed instead on exogenous factors—the

incompetence and irresponsible behavior of the central bank (Friedman,

1963, pp. 299-419).

From an Austrian perspective,

the same historical episode is seen quite differently (Hayek, 1975b, pp.

18-20; Robbins, 1934; Rothbard, 1963). The fact that there was virtually

no price inflation is irrelevant. There is no scope for the idea that the

monetary expansion simply accommodated real growth: real growth, in the

Austrian view, must be accommodated by real saving. The credit expansion

during the 1920s caused the rate of interest to be lower than it otherwise

would have been and thereby triggered a self-reversing process within the

market for capital goods. The actual self reversal came in 1929 causing

the economic downturn. This historical episode, then, is an illustration

of Hayek's story and not an exception to it.

Interpretations of history

have their counterpart in policy recommendations. Again, the differing

significance of price inflation is the basis for differences in preferred

policies. In the Monetarist view, so long as the price level is stable,

monetary expansion is not disruptive. Monetary expansion may even be necessary

to keep prices from falling during periods of real economic growth. In

the Austrian view, monetary expansion is a disruptive force, whether or

not the price level is changing as a result of the expansion. The particular

nature of the disruption will depend upon the particular form of the expansion.

The differing recommendations can be stated concisely in terms of the equation

of exchange and an assumed constant velocity of money. The Monetarist recommendation:

Increase the supply of money to match long-term, secular increases in real

output; the Austrian recommendation: Abstain from monetary expansion even

in periods of economic growth; increased credit should come only from increased

saving; increasing output should be accommodated by a declining price level.(34)

These policy differences suggest that the critical comparison of alternative

monetary dynamics is more than an idle exercise.

V. Further Implications

Our critical comparison has important implications about the way we

think about macroeconomic problems. The monetary dynamics envisioned by

Hayek provide a richer understanding of the market processes that might

be triggered by a monetary expansion, but the Austrian alternative may

at the same time render less serviceable—or even misleading—some of the

standard macroeconomic concepts. At issue, in particular, are the conventionally

defined categories of unemployment, the notion of "long and variable" monetary

lags, and the concept of "full" employment.

1. Cyclical and Structural Unemployment

Beginning with Keynes, it has been standard practice to identify a

number of categories of unemployment in order to isolate conceptually one

particular component of special interest. Cyclical unemployment is the

major focus of macroeconomic and monetary theory. Traditionally, theorizing

about what causes unemployment of this category or about how it might be

reduced or eliminated have been facilitated by impounding other categories

of unemployment in a ceteris paribus assumption. Frictional unemployment,

which is inherent in any market economy, is wholly attributable to the

existence of search costs. Unemployed workers of this category always find

employment, but not instantaneously. Institutional unemployment, such as

might be caused by minimum-wage legislation, may be lamentable, but it

is to be fully accounted for in terms of the legal constraints. These two

categories of unemployment can be conceptually separated from cyclical

unemployment, whether we accept Friedman's treatment of monetary dynamics

or Hayek's.

Structural unemployment

involves a geographical or occupational mismatch of workers and employment

opportunities. Unemployment of this sort could result from autonomous

shifts in consumer demand or from technological innovations. In Keynesian

and Monetarist formulations, structural unemployment is combined with frictional

and institutional unemployment, and all three are collectively impounded

in a ceteris paribus assumption. Keynes's views on unemployment

of these sorts are virtually identical to the "Classical" views of, say,

Cecil Pigou; they were spelled out by Keynes (1936, p. 6) only to make

clear what he was not talking about. Friedman (1976, p. 217) makes

use of these categories to locate the vertical long-run Phillips curve.

The natural rate of unemployment,

which is simply the market rate given frictions, mismatches, and institutional

constraints, serves as the base point from which to analyze cyclical unemployment.

Operationally, this last category is defined as a residual. Cyclical unemployment

is calculated by subtracting an estimation of the natural rate from the

measured unemployment rate. Friedman's story begins with an economy in

which all unemployed workers are "naturally" unemployed. Initially, then,

a monetary expansion gives rise to negative cyclical unemployment,

which persists until employer/worker wage-perception differentials are

eliminated. In symmetrical fashion, a monetary contraction—or disinflation—causes

the actual unemployment rate temporarily to exceed the natural rate. Eventually,

the natural rate is reestablished, but—more significant for the present

discussion—the rate of structural unemployment remains constant all the

while. The market process by which the economy deviates from and then returns

to the long-run Phillips curve creates no mismatches between workers and

employment opportunities. Money is neutral with respect to the structure

of the economy.

Hayek's story can begin

at the same point as Friedman's, but once the economy begins to react to

the monetary expansion, the strict dichotomy between structural unemployment

and cyclical unemployment can no longer be maintained. The self-reversing

process plays itself out in terms of changes in the structure of capital

and corresponding changes in the structure of employment. Friedman's initial

increase in employment becomes, in Hayek's story, an increase of some particular

kinds of employment at the expense of other particular kinds. If the new

money enters the economy through credit markets, the "forced saving," as

Hayek uses that term, is financing production for the more remote future

at the expense of production for the more immediate future. The structure

of employment opportunities is modified accordingly. The unemployment that

characterizes the later phase of the dynamic process, then, is structural

unemployment. It differs from the structural unemployment that existed

prior to the monetary expansion only in terms of the causal factors. But

operationally, structural unemployment caused by autonomous changes in

tastes and technology and structural unemployment caused by monetary disturbances

may not be separable categories of unemployment. (Does the waning of smokestack

industries reflect a technological shift towards an information-based economy,

or does it represent a structural hang-over from an earlier money-induced

boom?)

Further, expansion-induced

structural unemployment is likely to be long-lasting. The long run in Hayek's

formulation must be long enough so that all misallocated capital can be

liquidated and all capital/labor mismatches can be rectified. The amount

of time required may be so great as to make any propositions about long-run

neutrality highly misleading. (It would do violence to standard macroeconomic

terminology to categorize the Great Depression as an instance of "short-run

non-neurtality.")

Hayek (1977, p. 282; 1975a,

p. 44) does allow for the possibility that some cyclical unemployment may

not be structural unemployment. The reduction in incomes during the downturn

can—through the reduction in effective demand—have an aggravating effect

on the problem of unemployment. This is what Hayek refers to as the "secondary

deflation," or the "cumulative process of contraction." The unemployment

associated with the economy's spiraling downwards is the type of cyclical

unemployment dealt with by Keynes. Hayek's recognizing the possibilitly

of a secondary deflation does not, as some have suggested, constitute a

capitulation to Keynes. In fact, this problem was put into perspective

(1975b, p. 19) well before the appearance of The General Theory.

Rather, the fact that Hayek sees the Keynesian component of cyclical unemployment

as a secondary effect draws attention to the primary effect which Keynes

overlooked.

2. The Long and Variable Lag

We turn now from the nature of the unemployment that is caused by a

monetary disturbance to consider the length of time between the initial

injection of new money and the economy's eventual adjustment to it. As

an empirical summary, the Monetarist phrase "long and variable lag," (Friedman,

1969a, p. 238) is appropriate for both Friedman's and Hayek's account of

the monetary injection and its ultimate effect. But further reflection

on the two views of monetary dynamics reveals important differences in

this respect. First, the "ultimate effect," which marks the end of the

lag, refers to different things in the two views. As suggested above, the

overall level of prices may become fully adjusted to the increased quantity

of money long before the money-induced distortions in the structure of

capital (and labor) are fully eliminated. Thus, the short-run and long-run

Phillips curves may be separated by a much shorter span of time than the

short-run and the long-run Hayekian triangles.

Second, the basis for the

lag differs between the two views in an important way. Friedman's lag depends

upon how long it takes for workers to straighten out their misperceptions

of the real wage; Hayek's lag depends upon characteristics of the capital

structure—the degree of specificity and intertemporal complementarity of

the capital goods that make up the structure. Hayek's story suggests that

credit expansion is less disruptive (and involves a shorter adjustment

lag) in underdeveloped countries than in industrialized countries. This

accords with casual empiricism. Does Friedman's story suggest that workers

in underdeveloped countries have better and/or more quickly adjusting perceptions

of their real wage rates in comparison to workers in industrialized countries?

Third, there is an important

difference in the basis for the variability of the lag from one expansionary

episode to another within a given economy. For Friedman, the length of

the lag, being based on workers' misperceptions, is fundamentally indeterminate.

But it is not at all clear why it should take workers so long to straighten

out their misperceptions about the real wage and why it should take much

longer in some episodes than in others.(35)

For Hayek, the length of the lag will depend upon the particular way in

which capital and labor markets are distorted, which in turn depends upon

how the new money is injected. Monetary injections that discoordinate intertemporally

are more likely—precisely because of the temporal nature of the discoordination—to

involve longer lags than injections that discoordinate in some atemporal

way. This relationship between the method of injection and the likely length

of the lag helps to explain why the Austrian theorists have always seen

credit expansion, which was characteristic of the 1920s' boom, as particularly

troublesome, and why, in their study of this and other expansionary episodes,

they are as much or more interested in how—rather than how much—money was

injected.

3. "Full" Employment

Finally, we turn to the concept of "full" employment as used by Keynes

and Friedman in the light of the monetary dynamics as envisioned by Friedman

and Hayek. For Keynes, full employment is achieved so long as investors

are sufficiently optimistic or sufficiently moved by the "animal spirits,"

or so long as public works takes up the slack created by any insufficiency

of private spending. But the very nature of a self-reversing dynamic process—as

incorporated into the visions of both Friedman and Hayek—suggests that

the critical issue is whether or not a particular pattern of employment

is sustainable. In either vision any level of employment above the

full-employment level is clearly not sustainable. But in Friedman's

formulation, full-employment is—by construction—a sustainable level of

employment.

For Hayek, the level of

employment that corresponds to Friedman's full-employment may be sustainable

or it may contain the seeds of its own undoing (1975c, pp. 60-62). That

is, even though the real wage rate consistent with the underlying real

factors is correctly perceived by both employers and workers, the existing

capital structure may be inconsistent with the intertemporal pattern of

consumer demand and resource availabilities. The market process through

which these inconsistencies are discovered and remedied may involve a considerable

period of cyclical (structural) unemployment. Again, the circumstances

existing in the late 1920s can illustrate the distinction. In the Austrian

view, the economy was experiencing, in those years, unsustainable full

employment.

Friedman does recognize

that irresponsible monetary policies may eventually increase the natural

rate of employment. In two different pieces of analysis (1976, pp. 232-33

and 1977, pp. 459-60), he suggests the possible existence of a "positively

sloped Phillips curve." But in each case, new considerations not integral

to his story of the adjustment process are introduced to account for such

a possibility.(36) In neither case are

structural considerations—as conceived by Hayek—integrated into the dynamic

process envisioned by Friedman. Friedman's strict dichotomization of structural

and cyclical unemployment stands in the way of his recognizing the possibility

of full (in the operational sense) but unsustainable (in the Hayekian sense)

employment. Hayek's formulation, which involves an interplay between structural

and cyclical unemployment, allows for the recognition of such possibilities

and for the prescription of policy most conducive to sustainable full employment.

VI. A Summary View

Purely as an instrumentalist's device, it could be argued, Friedman's

story has served the Monetarists well. It put them onto the idea that the

Phillips curve trade-off is a short-run trade-off only. After this idea

was confirmed empirically (or properly, after it failed to be falsified

over many trials) the story itself became superfluous. The realization

that the empirically defined long-run Phillips curve is vertical is enough

to carry the day. It provides a strong basis for arguing that in the long

run, "nominal magnitudes do not influence real magnitudes" and for warning

against all attempts to exploit the trade-off offered by the short-run

Phillips curve.

Friedman's story and Hayek's

story differ sharply in methodological terms. Because of its instrumentalist

qualities, Friedman's story fares poorly as a source of insights about

the market process that translates a monetary injection into its ultimate

consequences; it fails to increase our understanding of any actual market

process. Hayek's story identifies the essential workings of the self-reversing

market process triggered by a monetary expansion in a way that sheds light

on the structure and timing of the pattern of unemployment caused by such

monetary disturbances. The Austrian insights contained in the Hayekian

triangles square with but go beyond the empirical regularities of Monetarism.

From a broader perspective,

Friedman's story represents a recognition of the intertemporal substitutability

of labor and of the possibility that monetary disturbances can interfere

with the intertemporal allocation of labor. Hayek's story represents a

recognition of the intertemporal complementarity of capital and of the

possibility that monetary disturbances can interfere with the intertemporal

allocation of capital. Viewed as such, the two stories are themselves not

substitutes, but complements.

References:

Ackley, Gardner 1978. Macroeconomics: theory and policy.

New York.

________ 1983. "Commodities and capital: prices and quantities."

American

Economic Review, 73.1 (March):1-30.

Bellante, Don 1983. "A subjectivist essay on modern labor

economics." Managerial and Decision Economics, 4.4:234-43.

Birch, Dan, Alan Rabin, and Leland Yeager 1982. "Inflation,

output, and employment: some clarifications." Economic Inquiry,

20.2 (April):209-21.

Blaug, Mark 1978. Economic Theory in Retrospect,

3rd ed. London.

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen 1959. Capital and Interest,

vol. 2 (1889). South Holland, IL.

Boland, Lawrence A. 1979. "A critique of Friedman's critics."

Journal

of Economic Literature, 17.2 (June):503-22.

Brimelow, Peter 1982. "Talking money with Milton Friedman."

Barron's,

62.43 (Oct. 25):5-6.

Butos, William 1985. "Hayek and general equilibrium analysis."

Southern

Economic Journal, 52.2 (Oct.)332-43.

Clower, Robert W. 1969. "The Keynesian counter-revolution:

a theoretical appraisal" (1965). In Robert W. Clower, ed., Monetary

Theory. Middlesex.

Darby, Michael 1976. Macroeconomics. New York.

Friedman, Milton 1953. "The methodology of positive economics."

In Milton Friedman, Essays in Positive Economics. Chicago.

________ 1969a. "The lag in effect of monetary policy."

(1956) In Milton Friedman, The Optimum Quantity of Money. Chicago.

________ 1969b. "Money and business cycles" (1963). In

Milton Friedman, The Optimum Quantity of Money. Chicago.

________ 1969c. "The optimum quantity of money." In Milton

Friedman, The Optimum Quantity of Money. Chicago.

________ 1969d. "The quantity theory of money: a restatement"

(1956). In Milton Friedman, The Optimum Quantity of Money. Chicago.

________ 1969e. "The role of monetary policy" (1968).

In Milton Friedman, The Optimum Quantity of Money. Chicago.

________ 1970. The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory.

London.

________ 1976. "Wage determination and unemployment."

In Milton Friedman, Price Theory. Chicago.

________ 1977. "Nobel lecture: inflation and unemployment."

Journal

of Political Economy, 85.3 (June):451-72.

Friedman, Milton and David Meiselman 1963. "The relative

stability of monetary velocity and the investment multiplier in the United

States, 1897-1958." In Stabilization Policies. London.

Friedman, Milton and Anna Schwartz 1963. A Monetary

History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton.

________ 1982. Monetary Trends in the United States

and the United Kingdom. Chicago.

Garrison, Roger W. 1984. "Time and money: the universals

of macroeconomic theorizing." Journal of Macroeconomics, 6.2 (Spring):197-213.

________ 1985. "Intertemporal coordination and the invisible

hand: an Austrian perspective on the Keynesian vision." History of Political

Economy, 17.2 (summer):309-21.

________ 1986. "Hayekian trade cycle theory: a reappraisal."

Cato

Journal 6.2 (Fall): 437-53.

Hicks, John R. 1946. Capital and Value, 2nd ed.

London.

________ 1967. "The Hayek story." In John R. Hicks, Critical

Essays in Monetary Theory. Oxford.

Hayek, Friedrich A. 1941. The Pure Theory of Capital.

Chicago.

________ 1948a. "The Ricardo effect" (1942). In Friedrich

A Hayek, Individualism and Economic Order. Chicago.

________ 1948b. "The use of knowledge in society" (1945).

In Friedrich A. Hayek, Individualism and Economic Order. Chicago.

________ 1967. Prices and Production, 2nd ed. (1935).

New York.

________ 1975a. Full Employment at Any Price, Occasional

Paper 45. London.

________ 1975b. Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle

(1933). New York.

________ 1975c. Profits, Interest, and Investment

(1939). Clifton, NJ.

________ 1977. "Three elucidations of the Ricardo effect."

Journal

of Political Economy, 77 (Mar./Apr.):274-85.

________ 1984. "The future monetary unit of value." In

Barry N. Siegel, ed. Money in Crisis. Cambridge, MA.

Hoover, Kevin D. 1984. "Two types of monetarism." Journal

of Economic Literature, 22.1 (Mar.):58-76.

Jevons, William S. 1970. The Theory of Political Economy

(1871). Middlesex.

Kaldor, Nicholas 1942. "Professor Hayek and the concertina

effect." Economica, ns 9(Nov.):359-82.

Keynes, John M. 1936. The General Theory of Employment,

Interest, and Money. New York.

Knight, Frank H. 1934. "Capital, time, and the interest

rate." Economica, ns 2 (Aug.):257-86.

Lachmann, Ludwig M. 1978. Capital and Its Structure

(1956). Kansas City.

Leijonhufvud, Axel 1968. On Keynesian Economics and

the Economics of Keynes. New York.

Lucas, Robert E. Jr. 1981. Studies in Business Cycle

Theory. Cambridge, MA.

Mises, Ludwig von 1953. The Theory of Money and Credit.

New Haven, CT. Originally published in German in 1912.

Musgrave, Alan 1981. "'Unreal assumptions' in economic

theory: the F-twist untwisted." Kyklos, 34.3:377-87.

O'Driscoll, Gerald P. Jr. 1977. Economics as a Coordination

Problem: The Contribution of Friedrich A. Hayek. Kansas City.

O'Driscoll, Gerald P., Jr. and Mario J. Rizzo 1985. The

Economics of Time and Ignorance. Oxford.

Phelps, Edmund S. 1970. "Money wage dynamics and money

market equilibrium." In Edmund Phelps et al., ed., Microeconomic Foundations

of Employment and Inflation Theory. New York.

Reder, Melvin W. 1982. "Chicago economics: permanence

and change." Journal of Economic Literature, 20.1 (Mar.)1-38.

Robbins, Lionel 1934. The Great Depression. London.

Robertson, Dennis H. 1949. Banking Policy and the Price

Level, rev. ed. New York.

Robinson, Joan 1972. "The second crisis in economic theory."

American

Economic Review. 62.2(May):1-10.

Rothbard, Murray N. 1975. America's Great Depression (1963).

Kansas City.

Wainhouse, Charles E. 1984. "Empirical evidence for Hayek's

theory of economic fluctuations." In Barry N. Siegel, ed., Money in

Crisis. Cambridge, MA.

Wagner, Richard E. 1979. "Comment: politics, monetary

control, and economic performance." In Mario J. Rizzo, ed., Time, Uncertainty,

and Disequilibrium. Lexington, MA.

Warburton, Clark 1966. Depression, Inflation, and Monetary

Policies: Selected Papers, 1945-1953. Baltimore.

Wicksell Knut 1936. Interest and Prices (1898).

London.

Notes:

1. Two related contributions are Hoover

(1984), who provides an insightful comparison between Old Monetarists in

the style of Friedman with the New Classicists in the style of Lucas, and

Butos (1985) who compares Hayek and Lucas in the context of a general-equilibrium

approach to business-cycle analysis. Although not originally conceived

for this purpose, the present paper can be seen as completing the trilogy

by comparing Hayek and Friedman on the issue of monetary dynamics.

2. We should note that the sharpness

of the labor-market/capital-market distinction that characterizes our paper

is not intended to suggest that Hayek has had nothing to say about labor

markets or that Friedman has had nothing to say about capital markets.

Hayek (1975a, pp. 15-29) specifically addresses the relationships among

"Inflation, the Misdirection of Labour, and Unemployment"; Friedman (1970,

p. 24-25) includes the existence of a cash-balance effect on asset prices

as one of the key propositions of Monetarism. Our paper focuses more narrowly

on a comparison of Phillips Curves and Hayekian Triangles as alternatives

bases for theorizing about monetary dynamics.

3. The article exhibiting Friedman's

agnostic stance was first published in 1963; the "engineering blueprint"

appeared in 1976 after having been presented at the Southern Economic Association

meetings two years earlier. Some might argue that a dozen or so years is

enough to transform vagueness into a blueprint. An alternative view is

that the agnosticism persists (see, for instance, Friedman, 1969c, p. 6);

the arguments in the later effort, which have their roots in his 1967 A.E.A

Presidential Address (1969e), are to be understood as Friedman's willingness

to take on his adversaries on their own turf. If this view is valid,

a distinction must be made between Friedman and his followers. Some Monetarists

(e.g. Darby, 1976, pp. 328-50) write as if Friedman's critical analysis

which demonstrates the absence of an exploitable long-run Phillips curve

is at the same time an exposition of the Monetarist view of the market

process which transforms monetary injections into increases in the price

level. Also, the formal analysis offered by Phelps (1970. pp. 124-66) is

similar to Friedman's critical analysis of the relationship between long-run

and short-run Phillips curves.

4. In other contexts, Friedman opts

for a more broadly conceived adjustment process in which asset prices change,

but he trivializes the corresponding quantity adjustments (e.g. that may

temporarily alter the structure of capital) as "first-round effects." See

Friedman and Schwartz (1982, ch. 2) and Friedman and Meiselman (1963, pp.

217-22).

5. Reder (1982) could be interpreted

as denying the significance in this respect of Knightian capital theory

for the development of the Chicago tradition. "The contribution to economic

thought with which Knight is most readily identified (theory of the firm,

uncertainty and profit, capital theory, social cost, etc.) are only

tangentially related to the Chicago tradition" (Reder, 1982, p. 6, our

emphasis). An anonymous referee has suggested that Reder's assessment is

compatible with our own: "The modern Chicago school interpreted Knight

so as to allow them to ignore capital theory."

6. See Friedman (1969c, pp. 4-7). Friedman

clearly recognizes that the money drop has to be perceived as a one-time

event. "Let us suppose further that everyone is convinced that this is

a unique event which will never be repeated." This essential assumption

separates Friedman from the New Classicists in terms of the issues that

each is addressing. The money drop in Friedman's analysis does not constitute

a "policy" in the New Classicist view. Further, Friedman's treatment of

expectations creates a certain internal tension in his own view if his

analysis is to explain more than a single episode of monetary expansion:

Market participants have adaptive expectations (about the price

level and real wages) during the period that the market is adjusting to

a money drop, but static expectations about the likelihood of a future

money drop.

7. As an alternative formulation, Friedman

does away with both the distribution effects and the differential income

effects by assuming "infinitely lived people" such that no transitory event

has any effect on permanent income (Friedman, 1969c, p. 6n). This alternative,

however, does not represent a net "relaxation" of simplifying assumptions;

it represents the replacement of one assumption with another, analytically

equivalent, assumption.

8. The exposition that follows draws

primarily from Friedman, 1976, pp. 213-37.

9. As Friedman makes clear, the shifting

of and movements along the curves are reversed if we take the employer's

point of view. The movement down the employer's demand for labor corresponds

to an apparent shift in the supply of labor (Friedman, 1976, p. 223).

10. The exposition of monetary dynamics

as seen by Hayek draws largely from his early writings (Hayek, 1967 and

1975b). Even the more advanced of these two books was intended only as

an outline (1967, p. vii). Hayek's monetary dynamics is based upon a theory

first set out by Mises (1953, pp. 339-66), which integrated the capital

theory of Böhm-Bawerk with a theory of interest-rate movements adapted

from Wicksell (1936).

11. The kernel of truth in the idea

of rational expectations is clearly recognized by Mises as early as 1953

as is demonstrated by the following passage on inflationary finance: "Here

the famous dictum of Lincoln holds true: You can't fool all of the people

all of the time. Eventually the masses come to understand the schemes of

their rulers. Then the cleverly concocted plans of inflation collapse....

[I]nflationism is not a monetary policy that can be considered as an alternative

to a sound money policy. It is at best a temporary makeshift. The main

problem of an inflationary policy is how to stop it before the masses have

seen through their rulers' artifices. It is a display of considerable naivete

to recommend openly a monetary system that can work only if its essential

features are ignored by the public" (Mises, 1953, p. 419). For a comparison

of Hayek's approach to the issue of expectations with that of New Classicism,

see Garrison (1986).

12. For a treatment of Austrian capital

theory that emphasizes these features, see Lachmann (1956).

13. Jevons (1970, pp. 229-36) had

earlier employed a triangular construction for similar purposes. Attempting