Conditional Probability, Independent Events, and Bayes' Rule

In this lesson you will learn the definition of conditional probability and what it means for two events to be independent. Conditional probabilities are then used to find the surprising answer to a practical problem and Bayes' rule is derived.

Conditional Probability and Independent Events

Suppose that a large classroom of statistics students is categorized by gender and year. The class has the following composition.

| FR | SO | JR | SR | |

| F | 3 | 28 | 54 | 15 | 100 |

| M | 0 | 15 | 30 | 5 | 50 |

| 3 | 43 | 84 | 20 | 150 |

Denote by \(S\) the set of all students in the class and by \(F,\) \(M,\) \(FR,\) \(SO,\) \(JR,\) \(SR,\) the set of all female students, male students, freshmans, sophomores, juniors, seniors, respectively.

A random experiment consists of selecting a student of the class such that each student has the same chance of being selected. Since all outcomes are equally likely, the probability of an event \(E\) can be calculated by the formula

\[P(E) = \frac{|E|}{|S|} .\]

In particular,

\[P(F) = \frac{|F|}{|S|} = \frac{100}{150}=\frac{2}{3},\]

\[P(SR) = \frac{|SR|}{|S|} = \frac{20}{150}=\frac{2}{15}, \mbox{ and}\]

\[P(F\cap SR) = \frac{|F\cap SR|}{|S|} = \frac{15}{150}=\frac{1}{10}.\]

In another random experiment, we select one of the seniors in the class. In that case the sample space is the set \(SR\) and the probability of an event \(E\) is calculated by \(|E|/|SR|.\) The rule \(P\) depends on the sample space and therefore it would be confusing to write \(P(E)\) for the probability of the event \(E\) given that the sample space is \(SR.\) Instead we use the notation \(P(E|SR)\) to indicate that the sample space is \(SR.\) Then

\[P(F|SR)=\frac{|F\cap SR|}{|SR|}=\frac{|F\cap SR|/|S|}{|SR|/|S|} = \frac{P(F\cap SR)}{P(SR)}.\]

This example motivates the following definition.

The conditional probability of \(A\) given \(B\) for events \(A\) and \(B\) is defined by

\[ P(A|B) = \frac{P(A\cap B)}{P(B)}\]

provided that \(P(B)\neq 0.\)

It follows directly from the definition of conditional probability that

\[P(A\cap B) = P(B)P(A|B)\]

and since \(P(A\cap B)=P(B\cap A)\) it also follows that

\[P(A\cap B) = P(A)P(B|A).\]

Multiplication Rule:

\[P(A\cap B) = P(B)P(A|B) = P(A)P(B|A).\]

Suppose that the conditional probability \(P(A|B)\)is independent of the event \(B\), that is \(P(A|B)=P(A).\) In this case the last equation is equivalent to the equation \(P(A\cap B) = P(A)P(B).\) This motivates the following definition.

Two events \(A\) and \(B\) are said to be independent if

\[ P(A\cap B) = P(A)P(B). \]

As an example, consider the random experiment of tossing a coin twice. The sample space \(S\) of all possible outcomes is \(\{HH, HT, TH, TT\}.\) Let \(A\) be the event of heads on the first toss and \(B\) the event of heads on the second toss. Then \(A=\{HH, HT\}\) and \(B=\{HH, TH\}.\) Suppose that all outcomes are equally likely, that is,

\[P(\{HH\}) = P(\{HT\}) = P(\{TH\}) = P(\{TT\}) = 1/4.\]

Then \[P(A)=P(\{HH, HT\}) = P(\{HH\})+P(\{HT\}) = 1/4 + 1/4 = 1/2,\]

\[P(B)=P(\{HH, TH\}) = P(\{HH\})+P(\{TH\}) = 1/4 + 1/4 = 1/2,\]

and

\[P(A\cap B)=P(\{HH\}) = P(\{HH\}) = 1/4.\]

Since \(P(A\cap B) = P(A)P(B),\) we conclude that the events \(A\) and \(B\) are independent.

Although independence of two events is a definition that needs to be verified, in practice one assumes that two events \(A\) and \(B\) are independent and uses the definition to calculate the probability of the event \(A \cap B .\)

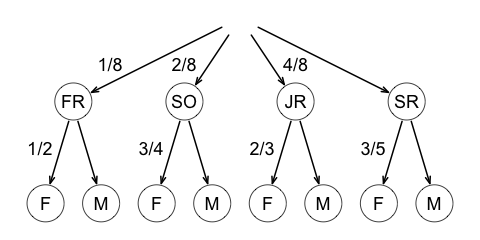

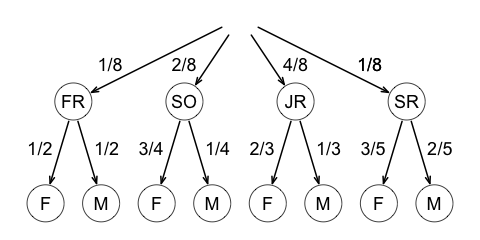

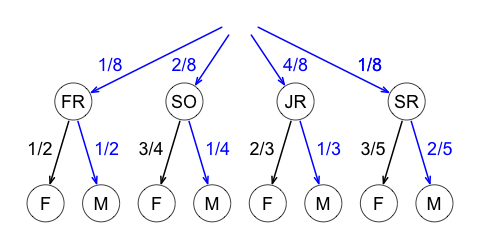

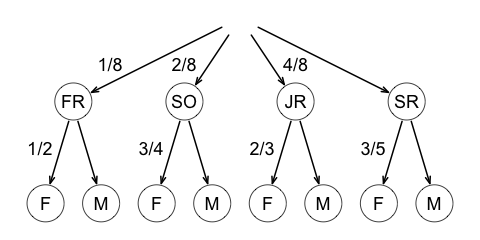

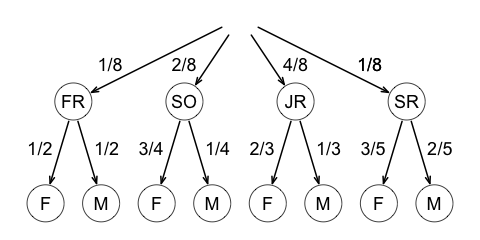

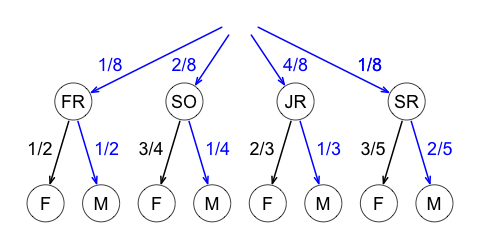

Suppose a class contains freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors. The proportions of freshmen, sophomores, and juniors are \(1/8,\) \(2/8,\) \(4/8,\) respectively. It is also known that \(1/2\) of the freshman, \(3/4\) of the sophomores, \(2/3\) of the juniors, and \(3/5\) of the seniors are female. What is the probability that a randomly selected student is male?

It is often helpful to illustrate a given problem containing conditional probabilities with a tree diagram.

First, we calculate the probabilities \(P(SR),\) \(P(M | FR),\) \(P(M | SO),\) \(P(M | JR),\) and \(P(M | SR)\) using the rule for complementary events.

The probability of the event \(FR\cap M\) can be calculated by the multiplication rule,

\[P(FR\cap M)=P(FR)P(M|FR)=\frac{1}{8}\cdot \frac{1}{2} = 1/16\]

that is, we multiply the numbers along the path.

The event \(M\) is the union of the four disjoint events \(FR\cap M,\) \(SO\cap M,\) \(JR\cap M,\) \(SR\cap M,\) and therefore

\[P(M) = P(FR\cap M)+P(SO\cap M)+P(JR\cap M)+P(SR\cap M).\]

We need to multiply along all the paths that lead to \(M\) and add up.

\[P(M) = \frac{1}{8}\cdot\frac{1}{2}+\frac{2}{8}\cdot \frac{1}{4}+\frac{4}{8}\cdot\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{8}\cdot\frac{2}{5} = \frac{41}{120}.\]

Bayes' Rule

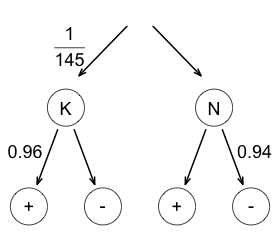

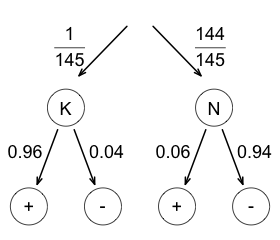

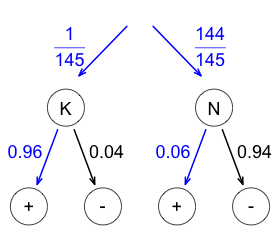

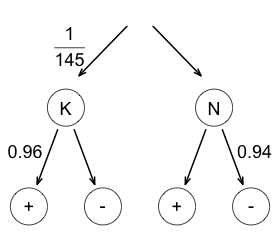

Suppose there is a very reliable test for a certain type of cancer. If I have this cancer then the test will be positive with probability 0.96. If I don't have the cancer, then the test will be negative with probability 0.94. Also suppose that 1 out of 145 people in my age group have that cancer without knowing it. I get the test and it comes out positive. What is the probability that I have cancer?

Denote the sample space by \(S\), the event of cancer by \(K\), the event of no cancer by \(N,\) the event of a positive test by \(\oplus,\) and the event of a negative test by \(\ominus.\) We want to know the conditional probability that I have cancer given that the test came back positive, that is, \(P(K|\oplus).\)

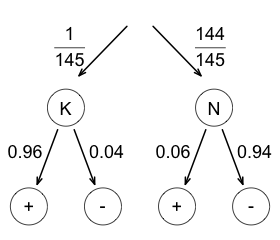

| First, draw a tree diagram. We are given \(P(K)=\frac{1}{145},\) \(P(\oplus | K) = 0.96,\) and \(P(\ominus | N) = 0.94.\) |  |

| Next, fill in all the missing probabilities in the tree diagram. Using the rule for complementary events we find that \(P(N)=\frac{144}{145},\) \(P(\ominus | K) = 0.04,\) and \(P(\oplus | N) = 0.06.\) |  |

By the definition of conditional probability

\[P(K|\oplus) = \frac{P(K\cap \oplus)}{P(\oplus)}.\]

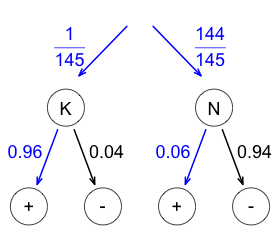

| The values for the numerator and the denominator can be found with the tree diagram.

\[P(K\cap \oplus) = P(K)P(\oplus | K) = \frac{1}{145}\cdot 0.96\]

\[\begin{align*}P(\oplus) & = P(K\cap \oplus)+P(N\cap \oplus)\\

& = \frac{1}{145}\cdot 0.96 + \frac{144}{145}\cdot 0.06\end{align*}

\] |  |

Therefore

\[\begin{align*}

P(K\ | \oplus) & = \frac{P(K \cap \oplus)}{P(\oplus)}\\

& = \frac{0.96\cdot (1/145)}{0.96\cdot (1/145)+0.06\cdot(144/145)}\\

& = 0.1,

\end{align*}\]

that is, the chance that I have the cancer is only 10%.

We can formalize the arguments given above as follows. Suppose that the sample space \(S\) is divided into two sets, \(B_1\) and \(B_2\). In other words, \(S=B_1\cup B_2\) and \(B_1\cap B_2 = \emptyset .\) Then for any set \(A\),

\[P(A) = P(A\cap B_1) + P(A\cap B_2) .\]

Since \(P(A\cap B_1)=P(B_1)P(A|B_1)\) and \(P(A\cap B_2)= P(B_2)P(A|B_2),\) it follows that

\[P(A) = P(B_1)P(A|B_1) + P(B_2)P(A|B_2) .\]

The last equation is known as The Law of Total Probability.

It follows from the definition of conditional probability and the law of total probability, that

\[P(B_1|A) = \frac{P(B_1\cap A)}{P(A)} = \frac{P(B_1)P(A|B_1)}{ P(B_1)P(A|B_1) + P(B_2)P(A|B_2)}.

\]

Similarly,

\[P(B_2|A) = \frac{P(B_2)P(A|B_2)}{ P(B_1)P(A|B_1) + P(B_2)P(A|B_2)}.

\]

The derived formulas for \(P(B_1|A)\) and \(P(B_2|A)\) are known as Bayes' formulas.

Rather than plugging into the Bayes' formula, I recommend that you start from the definition of conditional probability. According to this definition,

\[

P(K\ | \oplus) = \frac{P(K \cap \oplus)}{P(\oplus)}.

\]

We are given that \(P(\oplus\ | K) = 0.96\) (probability of positive test given cancer), \(P(\ominus\ | N) = 0.94\) (probability of negative test given no cancer) and \(P(K)=1/145\) (probability of cancer).

Let's calculate the numerator first using the multiplication rule.

\[P(K \cap \oplus) = P(\oplus | K)P(K) = 0.96\cdot (1/145).\]

Next, we calculate the denominator using the Law of Total Probability.

\[\begin{align*}P(\oplus) & = P(\oplus \cap K)+P(\oplus \cap N)\\

& = P(\oplus | K)P(K)+P(\oplus |N)P(N)\\

& = 0.96\cdot (1/145)+0.06\cdot(144/145). \end{align*}

\]

Therefore

\[\begin{align*}

P(K\ | \oplus) & = \frac{P(K \cap \oplus)}{P(\oplus)}\\

& = \frac{0.96\cdot (1/145)}{0.96\cdot (1/145)+0.06\cdot(144/145)}\\

& = 0.1.

\end{align*}\]

Another way to solve this problem is to create a two-way table that is consistent with the given information. One systematic way to do this is to find first the probabilities \(P(K\cap\oplus),\) \(P(N\cap\oplus),\) \(P(K\cap\ominus),\) and \(P(N\cap\ominus).\) With this information we can fill in a table for the joint distribution of the variables cancer

and result.

| positive | negative |

|---|

| cancer | \(P(K\cap\oplus) = \frac{1}{145}\cdot 0.96\) | \(P(K\cap\ominus) = \frac{1}{145}\cdot 0.04\) |

|---|

| no cancer | \(P(N\cap\oplus) = \frac{144}{145}\cdot 0.06\) | \(P(N\cap\ominus)= \frac{144}{145}\cdot 0.94\) |

|---|

Next, multiply each entry by a number that will change all the decimal numbers into an integer. In this example multiply each entry by \(14500.\)

| positive | negative |

|---|

| cancer | 96 | 4 |

|---|

| no cancer | 864 | 13536 |

|---|

Finally, add up all the rows and all the columns in the table.

| positive | negative | |

|---|

| cancer | 96 | 4 | 100 |

|---|

| no cancer | 864 | 13536 | 14400 |

|---|

| 960 | 13540 | 14500 |

|---|

Any of the conditional probabilities can now be determined from this table. For instance, the probability of cancer given that the test was positive is \(96/960\) or \(1/10.\)